Steel girders mark the border in the Parco Spina Verde above Paré

Once the Nazis had occupied Northern and Central Italy from September 8th 1943, escape across the border to Switzerland was the only option for many Jews seeking safety. But the Swiss had issued an anti-semitic decree back on August 13, 1942 that closed their borders to most Jews. It stated:

«… Political refugees, that is, foreigners who declare themselves as such when first questioned and can also provide proof, are not to be expelled. Those who seek refuge on racial grounds, as for example, Jews, are not considered political refugees».

This decree was not amended until July 1944 when fleeing from racial persecution was finally defined as a valid reason for granting asylum. Prior to that, Jewish migrants were at the mercy of the discretion or degree of compassion displayed by the local authorities. Rejection at the border would often lead to immediate arrest on re-entry into Italy with eventual transportation either from Milan or Fossoli to extermination camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau. The border running from Como to Varese would witness many of the resulting dramas and tragedies arising from the inconsistencies and changes in Switzerland’s asylum policy.

Vineyard just across on the Swiss side of the border in the municipality of Pedrinate

Following the declaration of the Badoglio government’s mismanaged armistice with the allies on September 8th 1943, there was a practical stampede of refugees seeking to avoid the imminent invasion of the Nazis, and Como was at the heart of it. Initially, and perhaps in recognition of the anti-semitic character of the existing restrictions, very few of these refugees were Jews.

A wire fence was erected along the length of the border dividing Lombardy from Switzerland. This has now been mostly dismantled. Here Guards are patrolling in the Province of Varese.

From the 9th to the 16th September the Como-Chiasso border went entirely unguarded and so thousands of recently disbanded troops crossed it. Alongside them came hundreds of allied POWs who had previously been released from most of the prison camps across Italy. Many civilians who had occupied the posts of ousted fascist government officials also considered they would be safer in Switzerland. Initially a relatively small number of Jews joined this exodus. Around 14,000 people fled into Canton Ticino over that 10 day period. Only 2.5% of those fleeing into Mendrisio (Como’s neighbouring province in Ticino) in September 1943 were Jewish. 87% were disbanded soldiers from the Italian Army and 6% were allied prisoners of war. All prisoners of war were accepted and interned for the duration of the war according to the Geneva Convention. If Badoglio’s government had given more forewarning and advice to its disbanded troops, they too could have been interned if presenting themselves in uniform. But the majority had discarded their uniforms and, without official credentials were beyond the safeguards of the Geneva Convention. As a result they were treated similarly to normal citizens with 23% being refused entry. The number of Jewish refugees may well have been relatively few but 40% of them were refused entry.

Male refugees were placed alongside ex-Prisoners of War in Bellinzona’s internment camp if they managed not to be turned back by the Swiss authorities.

That high figure of refusals reveals the Swiss Confederation’s policy at that time towards Jewish immigration. From 1938 onwards, the Swiss were concerned over the numbers of Jewish migrants, primarily from Germany and Austria, taking up temporary residence in Italy. Despite its later appalling record on Jewish expulsions during the Nazifascist era, Italy had welcomed Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe up until 1939. However they were allowed only temporary visas normally providing six months stay to arrange ongoing migration elsewhere. The fascist government had seen these visas as a source of revenue for the transportation companies that would take the migrants on to their final destination. The Swiss Government feared their ability to manage the potential influx of so many Jews residing over the border in Italy and so, to provide discouragement, tightened its policy towards permitting entry. The new restrictions on refugees from Italy allowed for the entry of soldiers, those already with Swiss citizenship, those foreigners who could claim close ties to Switzerland and those foreigners claiming their lives were in danger. But this last category was open to interpretation by local Police commanders.

The main crossing from Como into Switzerland was at Ponte Chiasso.

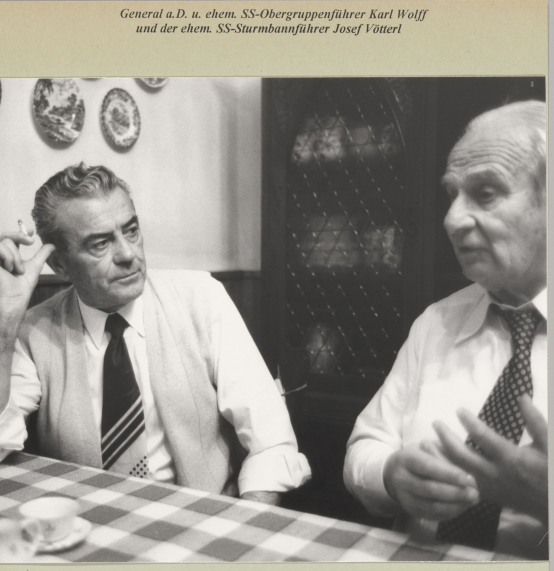

From 18th September 1943, the Nazis had taken control of the border crossing from Como into Chiasso and had set up their border police force assisted by the ‘Monte Rosa’ fascist militia. From that date, with the establishment of the SS Border Police headquarters in Cernobbio, the Holocaust had arrived in Como. Right from their arrival the Nazi’s primary concern in Como was to prevent the escape of Jews over the border. Adolf Eichmann himself had identified the Como crossing as requiring the immediate attention of Cernobbio’s SS chief, Josef Voetterl. Italy’s foreign Jewish community had also noted how Nazi behaviour towards them in Eastern Europe was being repeated here on Italian soil following the execution on September 22nd of a group of Greek Jews residing on Lake Maggiore at Meina. That group had been rounded up by an SS Battalion a mere six days after their occupation of Northern Italy.

Ex-SS Captain Josef Voetterl on left and SS Supremo in Italy Karl Wolff photographed in Voetterl’s home in Argentina in the 1970s.

As soon as the Nazis had control of the border crossings from Como to Varese, the Swiss Police chief, Heinrich Rothmund, used his discretion over the rights of entry to those avoiding the Holocaust. The standard policy at the time was to only grant asylum to women and children. No men were to be admitted. However, in response to the sudden increase in Jewish migration following the massacre at Meina, Rothmund limited access also to most women allowing in only those accompanying children under six years old.

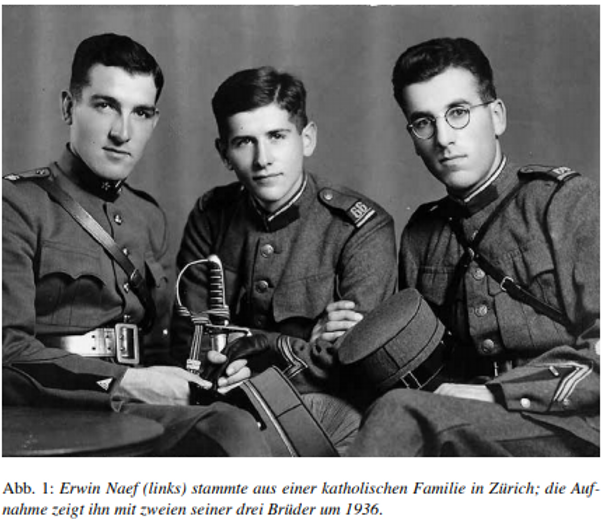

Lieutenant Erwin Naef on the left

The effect of this ruling led one Swiss border guard to report to his wife how he was left devastated by having to turn back migrants who knew, on returning to Italy, they would most likely face persecution and death. His name was Lieutenant Erwin Naef, a 30 year old businessman posted to guard the border in Pedrinate, a Swiss village just over the border that runs through the Parco Spina Verde north of Paré and Cavallasca. He wrote:

“The decision to reject the Jews as well is a terrible one….I was given the order to welcome children under six and their mothers and to turn away all the others. Girls and women between the ages of 15 and 30 have arrived, six in all, with tattered clothes, distraught faces, hungry and exhausted. I have informed the relevant superiors in Chiasso. The order is to push them back with the use of weapons. The girls knelt before me, crying and begging. I ordered my soldiers to fix bayonets and force them back to the border. […] Carrying out orders with weapons, however, was practically impossible. Because they lay on the ground, begging us to shoot them.”

He reported that his soldiers had apprehended 27 Jews on September 22 and 24, 1943. Seventeen were granted permission to stay with ten rejected and sent back to an unknown fate. These ten would have formed part of the 174 Jews in total sent back from Mendrisio during September 1943.

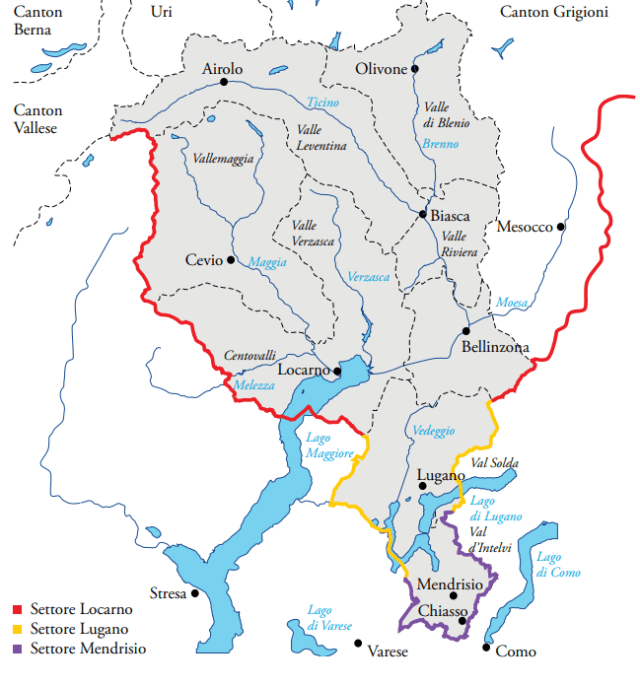

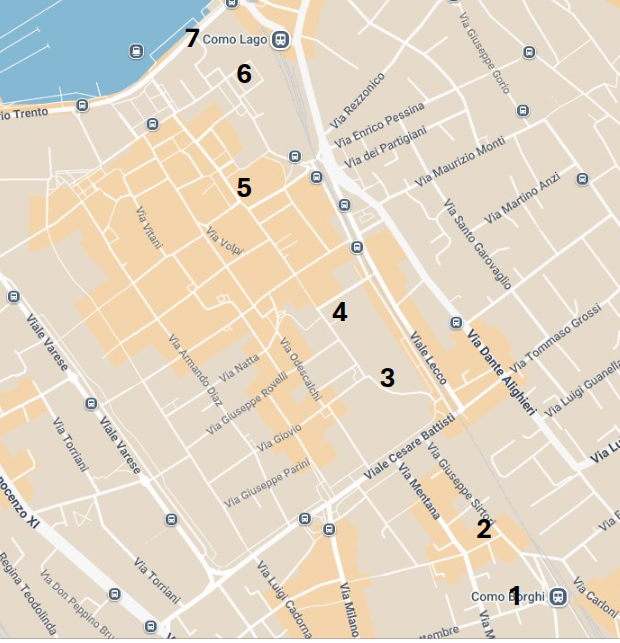

The data quoted in this article originates from records kept within the Mendrisio Customs area at tthe base of the map.

On the 24th September 1943, Erwin Naef again faced the task of having to turn back a distraught group of refugees. He called his superior in Chiasso begging to allow them all to enter but the response was no. He now faced a crisis of conscience unable to carry out the cruel command but unwilling to defy his military superiors. He asked to be relieved and replaced but he also secretly contacted the local mayor of Pedrinate, Tullio Camponovo. The mayor arrived within fifteen minutes with four local women trained in first aid and organised to assist refugees in distress.

Pedrinate

The town hall looked after the refugees overnight but Erwin Naef, on asking his superiors again to show some charity, was still told that under no circumstances could this group remain in Switzerland. Naef and the women helping the refugees did however come up with a solution. Since these refugees were Dutch nationals, perhaps some political pressure could be applied from the Dutch Consulate on the government in Bern. Phone calls were then made by Pedrinate’s priest to the Dutch consulate and, after much negotiation, the refugees were allowed to stay.

Tullio Camponovo’s daughter, Renata Camponovo

Fifty years later a Dutchman knocked on the door of Pedrinate’s town hall with a bunch of flowers asking for Tullio Camponovo. Unfortunately he had since died but his daughter was able to accept the flowers on her father’s behalf and to hear the stranger’s story. He was there representing his mother who had given birth to him in Lugano a few days after Tullio and Erwin had interceded to save her life.

Undoubtedly, the refugee acceptance policy at that time was inhumane. It took until July 1944 for the Swiss to recognise racism as a valid motive for asylum. Prior to that, safe harbour was at the discretion of the Police Chief who was free to determine local policy or to react under the pressure for compassion from determined people such as Erwin Naef.

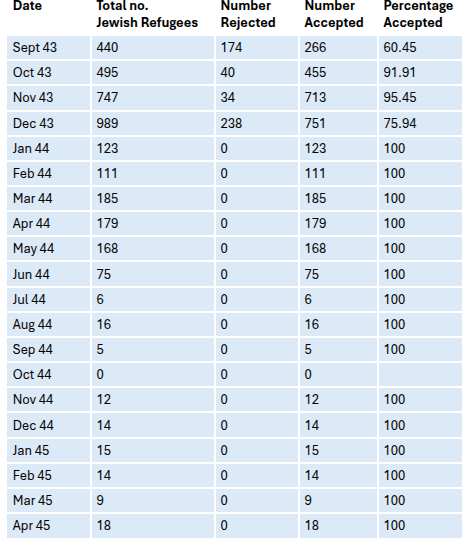

Fortunately this harsh interpretation of the Swiss Confederation’s asylum acceptance criteria did not last indefinitely. Debate amongst historians has raged now for some time on exactly how welcoming the Swiss were towards those victims of racism at risk of deportation from Italy to face almost certain death in a Nazi extermination camp. The table below shows the figures for Jewish migration as compiled solely for the Mendrisio Customs district over the length of the Nazi occupation of Italy. (The Mendrisio Customs district covered all the areas of clandestine crossings from Como to Varese). The figures were researched and published by the Swiss historian Adriano Bazzocco.

Data courtesy of Adriano Bazzocco. Accolti e respinti.

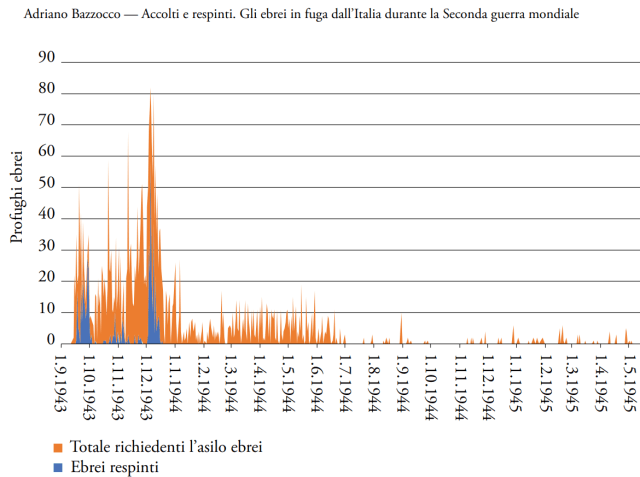

From this data we can see that the periods of high rejection were September and December 1943. The figure below gives greater detail of the numbers seeking asylum (in orange) and those rejected (blue).

The mid September peak was provoked by foreign Jews recognising that the Holocaust had now also arrived in Italy following the massacre of Greek Jews in Meina on Lake Maggiore. Subsequently Italy’s national Jewish population came to realise they also faced the same fate when, on 30th November 1943, the fascist government declared that all Jews, irrespective of nationality, were to be henceforth considered enemies of the state and were to be arrested and have their property seized. They had lived with anti-semitic racist laws since 1938 but they now faced the reality that not just their livelihoods were at risk but life itself.

The reaction of the Swiss authorities in accepting or rejecting Jewish migrants was not consistent over those first four months of the Nazi occupation. Their initial response to the first wave of foreign Jews was the most restrictive. This would be the period in which Erwin Naef recorded his acute discomfort in having to return desperate asylum seekers back over the border. However an equal number of Jews sought sanctuary over October 1943 but relatively few were rejected. Even more sought sanctuary in November 1943 but even fewer were rejected. Yet harsh terms were reinstated in December in response to the largest wave of refugees seeking safety after the 30th November declaration. Yet, from the following January 1944 until the end of the war, not a single request for asylum was rejected even if the actual racist grounds for acceptance was not officially recognised until July 1944.

From December 1943 to January 1945, 23 trains left Platform 21 of Milan’s Central Station containing mainly Jews but also partisans and political dissidents with their direct destination Auschwitz. The platform is now a memorial to the Holocaust.

For any men, or even those women unaccompanied by young children, crossing the border over the first four months of the Nazi occupation was a major gamble. There was the hope of salvation and safety from the Holocaust or the risk of being pushed back over the border into nazifascist Italy. For those pushed back, they would face immediate arrest, imprisonment, deportation and death if they fell into the hands of the Nazi border police or the fascist militias patrolling the border. If they managed to reenter unnoticed, they could make another attempt to cross to safety later, perhaps when the Swiss had assumed a more humane policy to acceptance. This is what happened to some of the party Erwin Naef had been forced to reject at Pedrinate back on September 22nd 1943.

ARV946773 S.M. Albert I Roi des Belges, Adel Belgien, Portrait; Private Collection; © Arkivi UG All Rights Reserved.

Among those Erwin Naef had ordered back over the border on 22nd September 1943 was the family of Wilhelm Gluek aged 30. He was accompanied by his wife Vera, aged 23, his mother-in-law Irene, aged 46 and his sister-in-law Mira, aged 21. All four were refused entry, allowing only his mother Lenka, aged 58, his sister Ella, aged 32 and his two-year old daughter to stay. Erwin Naef had begged his superior Captain Burnier to allow the whole family group to stay but Burnier, acting under orders from the Police Chief Rothmund, refused Erwin Naef’s pleading. The remainder of the Gluek family managed to avoid capture on their return to Italy and indeed made a fresh attempt to cross the border on 1st January 1944. As our table above shows, no requests for admission were denied to Jews on that and all subsequent dates during the war. The Gluek family was thus reunited safely free from the threat of deportation within the Swiss Confederation.

At least in the Mendrisio district, from the data researched by Adriano Bazzocco, it is possible to state that Switzerland, after a poor start, managed to restore its humanitarian reputation as a safe haven for the persecuted. But only once it overcame its initial fear of overpowering numbers and the pervading aspect of anti-semitic racism infecting both it and most of the rest of Europe at the time.

Plaque inserted in the pavement in front of Guido Levi’s home on Via Castel Morrone, Milan. These plaques are placed around Europe outside the homes of those murdered in the Holocaust. This initiative was introduced by German artist Gunter Demnig as a means of confronting those who deny the Holocaust. The German name for these plaques is ‘Stolpersteine’. Those for Guido Levi and his wife Luigina Ascoli were laid on 29th January 2021 during the Covid lockdown.

References

Adriano Bazzocco. Accolti e respinti. Gli ebrei in fuga dall’Italia durante la Seconda guerra mondiale: nuove analisi e nuovi dati. https://adm-stabio.ch/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2021-AST-Accolti-e-respinti.pdf

Scomazzon, F. (2022). La linea sottile: Il fascismo, la Svizzera e la frontiera. Donzelli Editore.

Further Reading

We have written a number of articles recounting the impact of the Holocaust in the Como area including accounts of those who made a safe crossing into Switzerland and those who did not. They include:

Escaping the Holocaust: Hiding from Home in Varese

Como to Chiasso – Trying to Escape the Holocaust

Heroism and Disaster in the Vallassina – Holocaust Memorial Day, January 27th

Como’s ‘Viaggi della Salvezza’ – In Memory of the Holocaust

Testimonies and Remembrance: Como Recalls the Shoah

Escape to Switzerland via Monte Bisbino

The walk described in Parco Spina Verde: Walking the Border Back to Como describes the area north of Paré following the border with Switzerland and Pedrinate

Conclusion

Conclusion

The way we see Piazza Duomo and the attached Piazza Grimoldi today is mostly thanks to Federico Frigerio. The illustration below marks each of his changes and interventions.

The way we see Piazza Duomo and the attached Piazza Grimoldi today is mostly thanks to Federico Frigerio. The illustration below marks each of his changes and interventions.

Other crests exist above doorways on both sides of Via Balestra and above the entrance to Palazzo Odescalchi on Via Rodari but are so worn with age that it is impossible to make out their designs. These all date from the Renaissance period and adorn doorways decorated in contrasting bands of Varenna and Musso marble, as was quite commonly used on many of Como’s Renaissance palazzi. The more recent crest above the doorway of the bar at the theatre end of Via Porta shows an anchor and the staff of Mercury – a caduceus- leading to the idea that the householder was a merchant involved in shipping on the lake.

Other crests exist above doorways on both sides of Via Balestra and above the entrance to Palazzo Odescalchi on Via Rodari but are so worn with age that it is impossible to make out their designs. These all date from the Renaissance period and adorn doorways decorated in contrasting bands of Varenna and Musso marble, as was quite commonly used on many of Como’s Renaissance palazzi. The more recent crest above the doorway of the bar at the theatre end of Via Porta shows an anchor and the staff of Mercury – a caduceus- leading to the idea that the householder was a merchant involved in shipping on the lake.

All of this mostly good fortune came to an end the moment Raymond could not resist seeing what Melusine did every Saturday. Spying on her through a keyhole, he saw her lower body transformed into a serpent. Later he could not help berate her by calling her ‘Serpent’. At this point Melusine developed wings and flew away.

All of this mostly good fortune came to an end the moment Raymond could not resist seeing what Melusine did every Saturday. Spying on her through a keyhole, he saw her lower body transformed into a serpent. Later he could not help berate her by calling her ‘Serpent’. At this point Melusine developed wings and flew away.  Another interesting fable mixing mythology with early historical accounts and also including mentions of the Crusades was the 14th century account of Richard Coer de Lyon, a magical telling of the life of this Plantagenet King of Western France and England. In this version, King Richard’s father, Henry II, does not marry Eleanor of Acquitaine but someone called Cassodorien, the daughter of the King of Antioch. They have three children, namely Richard (the later King), John (responsible for Magna Carta) and a daughter named Topyas. History records Richard’s exploits and also those of bad King John but Topyas is never mentioned because she was whisked away by her mother who sprouted wings and took to flight when she was forced one day to sit through an entire Mass.

Another interesting fable mixing mythology with early historical accounts and also including mentions of the Crusades was the 14th century account of Richard Coer de Lyon, a magical telling of the life of this Plantagenet King of Western France and England. In this version, King Richard’s father, Henry II, does not marry Eleanor of Acquitaine but someone called Cassodorien, the daughter of the King of Antioch. They have three children, namely Richard (the later King), John (responsible for Magna Carta) and a daughter named Topyas. History records Richard’s exploits and also those of bad King John but Topyas is never mentioned because she was whisked away by her mother who sprouted wings and took to flight when she was forced one day to sit through an entire Mass.