Panorama of the Como leg of Lake Como, ca 1850

The Grand Tour was initially a key part of the finishing education for upper class Englishmen intended to acquaint them with the classical world and its rediscovery through the Italian Renaissance. Interest in the classics declined at the turn of the nineteenth century as the influence of Romanticism grew. And so Lake Como became an increasingly popular destination for those seeking the ‘sublimity’ of its dramatic landscape. Throughout the century a distinguished list of international writers, artists and musicians recorded and published accounts of their visit to the lake. Excerpts from twenty of these accounts have now been translated into Italian and published by Edizioni Sentierodeisogni with the title ‘Lago di Como Grand Tour’. This book serves as a great reminder of our cultural heritage and of what lies at the heart of the lake’s ongoing appeal to the ever increasing number of visitors from abroad. Here below is a brief selection of some of the entries in this fascinating collection.

The Poets

The first excerpt in the collection is taken from the father of Romanticism, William Wordsworth, in his Descriptive Sketches, first published in 1793 with a final edition in 1836. This poem describes his journey over the Alps and along the banks of our lake undertaken in 1790. From its total of 670 lines of rhyming couplets, 70 are dedicated to the lake, with 30 of them posted below:

More pleased, my foot the hidden margin roves

Of Como, bosomed deep in chestnut groves.

No meadows thrown between, the giddy steeps

Tower, bare or sylvan, from the narrow deeps.

To towns, whose shades of no rude noise complain,

From ringing team apart and grating wain

To flat-roofed towns, that touch the water’s bound,

Or lurk in woody sunless glens profound,

Or, from the bending rocks, obtrusive cling,

And o’er the whitened wave their shadows fling

The pathway leads, as round the steeps it twines;

And Silence loves its purple roof of vines.

The loitering traveler hence, at evening, sees

From rock-hewn steps the sail between the trees;

Or marks, ‘mid opening cliffs, fair dark-eyed maids

Tend the small harvest of their garden glades;

Or stops the solemn mountain-shades to view

Stretch o’er the pictured mirror broad and blue,

And track the yellow lights from steep to steep,

As up the opposing hills they slowly creep.

Aloft, here, half a village shines, arrayed

In golden light; half hides itself in shade:

While, from amid the darkened roofs, the spire,

Restlessly flashing, seems to mount like fire: 0

There, all unshaded, blazing forests throw

Rich golden verdure on the lake below.

Slow glides the sail along the illumined shore,

And steals into the shade the lazy oar;

Soft bosoms breathe around contagious sighs,

And amorous music on the water dies.

The edition of the Critical Review published in August 1793, is somewhat scathing of Wordsworth’s style, and whilst stating that his lines on Como are some of the best, the reviewer clearly dislikes the overall effect stating ‘his lines are often harsh and prosaic; his images ill-chosen, and his descriptions feeble and insipid.’ The author of the article in the Monthly Review published in October 1793 is even more critical as he opines: ‘More descriptive poetry! Have we not yet enough? Must eternal changes be rung on uplands and lowlands, and nodding forests, and brooding clouds, and cells, and dells, and dingles?’ Possibly a response shared by generations of future schoolchildren!

Como engraved by Samuel Prout 1839

Other poets sufficiently enchanted by the lake to attempt to capture its charm include Samuel Rogers, a contemporary of Wordsworth, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who became enamoured of Cadenabbia during his stay in 1868. In a letter to a friend and colleague, James T. Field, he states:

‘I last wrote to you from Lugano. From that pleasant place we moved to another even more pleasant; namely Cadenabbia on Lake Como. That was Italy as suggestive as Italy can be when it tries. The weather was delightful, neither too hot or too cold but delightfully temperate with all the necessary elements for creating an ideal climate. One did not see or feel any insects! And a gentle current of air rose and fell on the lake, no more than needed to make a small breeze. No road goes to Cadenabbia, only a footpath that follows the lake front, between it and numerous villas… It has been difficult to leave here. Arriving here just for the night we stayed for a week.’

Mary Shelley’s first trip to Italy in the company of her husband and young children was to end tragically with the deaths of her husband and her second and third child. Back in April 1818, and well before her husband’s death in 1822, the Shelleys were planning their stay at the Villa Pliniana, outside of Torno. It was then almost a ruin but one located magnificently on the lakeside, in almost constant shade and with its famous stream cascading intermittently though its structure. The Grand Tour collection includes a letter sent by Percy Shelley to his friend Lord Byron, then in Venice, inviting his fellow poet to stay with the couple. He writes: ‘If you have never seen this delightful and sublime scenario, I think it would be worth your while. Would you like to spend a few weeks with us? Our way of living remains the same as you will remember it when we were in Geneva, and the spot we have chosen (the Villa Pliniana) is isolated and surrounded by magnificent landscape, with the lake at our feet. ‘

Villa Pliniana, now a luxury hotel

Mary Shelley would later return to Italy and to Lake Como in 1840 in the company of her only surviving child when she spent considerable time in Cadenabbia. (Our article entitled Holidaying on Lake Como: In the Footsteps of Mary Shelley describes her stay in detail.)

The Novelists, Essayists and Assorted Writers

As would be expected most of the other entries in the collection are from established authors and include Gustave Flaubert, Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Warton, August Strindberg and Franz Kafka.

Isola Comacina by Sophia Hawthorne, 1839. Note her fanciful edition of a Roman temple in Sala Comacina

There is also an entry for the author of ‘The Scarlet Letter’, Nathaniel Hawthorne who came to appreciate Lake Como through a couple of paintings created and gifted to him as an engagement present by his fianceé Sophia Amelia Peabody in 1840. Neither Nathaniel nor his wife had ever or would ever visit Lake Como but the two paintings – one of Menaggio and the other of Tremezzina taking in Bellagio and Isola Comacina – took pride of place in their matrimonial home ‘The Old Manse’ in Concord, Massachusetts. They are currently on show at the nearby Peabody Essex Museum.

Sophia Hawthorne, Villa Menaggio 1840

Here is an excerpt from his letter to Sophia dated January 24th 1840 on receipt of the two paintings:

Ownest Dove,

Your letter came this forenoon, announcing the advent of the pictures; so I came home as soon as I possibly could—and there was the package! I naturally trembled as I undid it, so eager was I to behold them. Dearissima, there never was anything so lovely and precious in this world. They are perfect. So soon as the dust and smoke of my fire had evaporated, I put them on the mantelpiece, and sat a long time before them with clasped hands, gazing, and gazing, and gazing, and painting a fac-simile of them in my heart, in whose most sacred chamber they shall keep a place forever and ever. Belovedest, I was not long in finding out the Dove in the Menaggio. In fact, she was the very first object that my eyes rested on, when I uncovered the picture. She flew straightway into my heart—and yet she remains just where you placed her. Dearest, if it had not been for your strict injunctions that nobody nor anything should touch the pictures, I do believe that my lips would have touched that naughty Sophie Hawthorne, as she stands on the bridge. Do you think the perverse little damsel would have vanished beneath my kiss? What a misfortune would that have been to her poor lover!—to find that he kissed away his mistress. But, at worst, she would have remained on my lips. However, I shall refrain from all endearments, till you tell me that a kiss may be hazarded without fear of her taking it in ill part and absenting herself without leave.

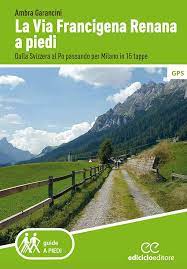

One year later (1841) Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx’s collaborator and co-author of ‘The Communist Manifesto’, recorded his visit to Lake Como under the pseudonym Friedrich Oswald in an article entitled ‘Lombardische Streifzuege’. He followed the route of the Via Francigena Renana down from Coira (Chur) to Chiavenna. He contrasts the drama of the gorge of the Via Mala as the Rhine cuts a vertiginous passage through the rocks from the heights of Splugen with the warm, and fertile valley of Chiavenna: In his words as he nears Chiavenna:

‘Finally the valley opens up and, turning a curve, one sees rising ahead the tower of Chiavenna (Claewn in German), one of the main cities in the Valtellina. Chiavenna is already a completely Italian city, with its tall houses and narrow streets, where in every corner one hears colourful interjections in Lombard dialect.

Whilst we were dedicating our attention to an Italian dinner washed down with a Veltliner (Engels seemed particularly appreciative of this particular wine variety), the sun disappeared behind the Rhaetian Alps. We then climbed aboard an Austrian carriage going to Lake Como with an Italian driver and and a carabiniere as escort…..Later we crossed a green area of vineyards, with vine runners trailing over pergolas and the tops of mulberry trees. The warm italian air led me to recognise, ever increasingly, the charm of a land and nature still unknown but long dreamed about: a charm that ran through my body as a sweet shiver, whilst my spirit kept returning to all the extraordinary beauty on offer to my gaze. And so, full of happiness, I fell asleep.’

Available on Amazon.it

Those wishing to trace the route taken by Engels from Coira to Como can follow the Guide to the Via Francigena Renana published by Iubilantes.

Lady Morgan, born 1781 in Ireland to a Catholic father and a Protestant mother, became a renowned author, a champion of women’s emancipation and supporter of national independence movements including support for revolutionary France and Italian liberation from Austrian rule. Her travelogue on Italy was published in three volumes in 1821. Her volumes on Italy aimed to go beyond a travel guide to ‘contribute to the regeneration of a country oppressed by foreign occupation’ as of course, was her native Ireland. Thirty pages of her travelogue are dedicated to Como. She reported on a city of narrow, run-down malodorous streets, of a population kept in thrall of religious superstition and a local economy throttled by alien restrictions.

Como, 1850 Engraving by Giuseppe Elena

Chapter IX of Italy, Volume 1 (1821) is dedicated in its entirety to a description of Como. She introduces the chapter with an astute and still highly relevant paragraph on the city’s geo-political significance:

‘Above all the Northern districts of Italy, Como, its lake, its city, and its mountains, seem pre-eminently distinguished by historical interest. The natural beauty of its scenery, its border position on the frontiers of states varying in clime, language, and soil, early rescued this Eden of Lombardy from obscurity, and rendered its magnificent solitudes the sites of many contests, and the witnesses of many crimes.’

While almost all other travellers seem entirely focussed on the glory of the landscape, Lady Morgan adds perceptive commentary on the political and economic realities of what is essentially an Austrian dominated garrison town. Once reading her account of the numerous barracks, the strict curfews and the atmosphere of espionage and observation imposed by its ‘imperial masters’, you come to more readily appreciate the significance of Como’s acts of rebellion later in the nineteenth century such as the ‘5 Giornate’ in 1848, with the subsequent surrender of the Austrian garrison in Piazza Vittoria and Garibaldi’s victory at the Battle of San Fermo in 1859. And as for the ongoing series of ‘contests and crimes’, it’s far from accidental that Lake Como would ‘witness’ the executions that brought an end to the nazifascist conflict in 1945.

On the local economy, Lady Morgan states: ‘The principal resources of this ‘Regia Città’ are the manufacture of a little silk and cotton (carried on under every restriction that can check its success) and the adventurous enterprises of smuggling, by far the most prospering and profitable of its ways and means.’ Silk production was to grow immensely in importance as the century progressed (and following liberation from Austrian rule) such that silk finishing is still as important to the local economy today as is tourism. As for smuggling, that remained a constant right into the 1970s and 80s, when a day trip to the lake from Milan would often include the purchase of a carton of contraband cigarettes.

The charm and beauty of Lake Como, from Careno

But, notwithstanding the socio-political issues, even Lady Morgan could appreciate the glories of the local landscape: ‘But whatever the internal defects of Como, however gloomy its streets and noxious its atmosphere, the moment that one of the little boats which crowd its tiny port is entered, and pushed from the shore, the city gradually becomes a feature of peculiar beauty in one of the loveliest scenes ever designed by nature.’

Canova’s Cupid and Psyche in Villa Carlotta

An appreciation of Canova’s ‘Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss’ in Villa Carlotta led the author of Madame Bovary into an ardent embrace of the statue, as recorded in his Notes de Voyages published in 1910. Flaubert shared Liszt’s love of Bellagio and in this was preceded by Mark Twain who wrote his account of his stay on Lake Como in ‘The Innocents Abroad or the New Pilgrims’ Progress’ published in 1869. The translation into Italian of the Mark Twain excerpts, for inclusion in this current collection, was done under instruction of their teacher Laura Gornati by pupils of Class 4F of the Istituto Vanoni di Menaggio. Another American visitor to the same area of the lake was Henry James who included his account of up to forty years of visits to Italy in ‘Italian Hours’ published in 1909.

The novel by Alexei Tolstoy set in and around Como

The collection includes an excerpt from ‘The Vampire’ – a gothic melodrama set in Como and written in 1841 by Alexei Tolstoy, an ancestor of the more famous Russian author, Leo Tolstoy. Alexei truly loved Italy and Lake Como. He was said to have come to Como to undertake a course of treatment called ampelo or grape therapy designed to rid the body of toxins and cure cardiovascular issues. His treatment centre was in Tavernola between Como and Cernobbio. The area was covered in vineyards in his time. Apart from following this strange course of treatment which involved eating copious quantities of grapes, he had time to fall in love with Peppina, the daughter of one of the guardians of Villa Olmo. Both the villa and Peppina feature in Tolstoy’s novella.

Cernobbio’s vineyard. One of the few remaining vineyards near to Como.

The famous Nobel laureate Albert Einstein was another visitor to the lake in the company of his fianceé Mileva Maric who recorded their trip in 1901 in a series of letters to her friend, Helene Savic. Albert was staying with family in Milan and Mileva was studying in Zurich when they met up on 5th May 1901 at Como’s San Giovanni station, from where they journeyed up the lake taking in the key resorts. During their holiday, Mileva became pregnant and their child was then born at the end of January or start of February 1902 but was immediately entrusted to Mileva’s friend, Helene. From that point on, the life and fate of Albert and Mileva’s child was a mystery with the likeliest outcome being its adoption by Helene and a change of name. Like many others before her, Mileva and Albert were impressed by Villa Carlotta:

‘At Cadenabbia we stayed for a while and visited Villa Carlotta. I don’t know how to describe to you the splendour we found everywhere. You know, some of Canova’s works are displayed there and there is a beautiful garden that remains in my heart, no less because it is forbidden to pick a single flower. It was the most splendid spring when we visited and we could not have imagined that the day after we would be riding a sledge in a whirl of snow.’

Einstein was later famously to refuse an invitation to come to Como, six years after being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, to attend the gathering of Nobel prizewinners in 1927 organised to celebrate the centenary of the death of Alessandro Volta. His gesture was made in opposition to the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini. He did however visit the Tempio Voltiano in 1933, shortly before his emigration to the United States, to honour Como’s most famous son.

The gathering of Nobel prizewinnners and physicists at the 1927 Congresso dei Fisici which Einstein did not attend in opposition to the fascist regime.

The other authors included in this collection are August Strindberg, Edith Warton, Franz Kafka, Stefan Zweig and Hermann Hesse. The collection has been put together by Pietro Berra, a local poet and journalist responsible for editing the cultural supplement of the local paper ‘La Provincia’. He has been ably assisted by professional translators as well as, in the case of Mark Twain, local schoolchildren. Pietro Berra has previously worked with local schools in translating and publishing Mary Shelley’s account of her second stay in Italy in the company of her one surviving child.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Pietro Berra for his initiative in researching and publishing this collection of extracts from this rich variety of famous visitors. He is responsible for a number of other initiatives which go to make evident the historical cultural links of our territory. These include establishing the Lake Como Poetry Way and its Little Free Libraries.

This article is based on material available in Lago di Como Grand Tour, edited by Pietro Berra and published by Edizioni Sentiero dei sogni.

Other material and initiatives written, edited or organised by Pietro Berra are described in www.sentierodeisogni.it

References

The entire test of Wordsworth’s Descriptive Sketches can be found at archive.org as can Lady Morgan’s Italy Volumes 1 – 3.

Further Reading

An account of Mary Shelley’s second stay on Lake Como can be found at Holidaying on Lake Como: In the Footsteps of Mary Shelley. This article is also based on material published by Pietro Berra.

More information on the ancient route across the Alps known as the Via Francigena Renana is available from Iubilantes’s site.

Forgotten American writer Joaquin Miller, a contemporary and friend of Mark Twain, wrote an amusing poem called “Como” in the 1870s that reads like a Spaghetti Western.

https://kbc-cwc-wir-jmp.blogspot.com/2025/11/miller-in-italy-lake-como.html

LikeLike

I am going to pass this link on to Pietro Berra who collects references from authors and poets to Como and its lake. Thanks.

LikeLike

Wonderful post! I visited for the first time yesterday, and started reading The Betrothed after seeing the Manzoni yacht in the harbor 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Kristen, I hope you enjoy The Betrothed. You are now voluntarily reading the book all Italian schoolchildren have to study!

LikeLike