Gian Giacomo de Medici, detto Il Medeghino

Gian Giacomo De Medici was born in 1495 in Milan as the eldest son of Bernardino De Medici and Cecilia Serbelloni. His family was not related to the better known Medici of Florence. He was the eldest of Bernardino and Cecilia’s ten children.

The family background was modest. His father acted as a tax and debt collector to the Duke of Milan, Massimiliano Sforza, to whom he also owed money. When the French captured the dukedom in 1515, they imprisoned Bernardino and confiscated all his possessions leaving the family destitute. Yet by the time of Gian Giacomo’s death in 1555, he had himself become a marquis, the Serbelloni family had become ennobled, his brother had become Pope Pius IV and his sister had given birth to the future Cardinal Carlo Borromeo – all thanks to Gian Giacomo and his career as Il Medeghino, one of the most successful condottieri in the Renaissance period.

Print by Franz Hegi of a painting by Johann Jakob Wetzel published in ‘Voyage Pittoresque au Lac de Como’ in 1822.

Late Renaissance in Lombardy

Il Medeghino’s castle in Musso was fortified from the port up to where the Church of Saint Eufemia now stands. This promontory gave him a view north and south down the lake, and the fortifications made it invincible. The castle was eventually destroyed by the army of the Swiss Federation once Il Medeghino had signed a peace treaty with Francesco II Sforza in 1532.

In spite of all the artistic and scholarly achievements of the renaissance, the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in Italy were highly unstable. This was due to the competing interests of those seeking to gain territory and control over the host of individual dukedoms and city states across the country. The major contestants were the Papacy, the French royal family, and the Spanish who also had possession of the Holy Roman Empire. Caught in this complex web of intrigues and alliances were the dukedoms themselves such as the Sforza in Milan, the Venetian republic, the Swiss Federation and the Grisons. The Grisons were not fully integrated into the Swiss Federation until the 1520s and were constantly seeking to extend their territories down the Valtellina and the Val Chiavenna so as to gain control over the top end of Lake Como. For the French or Spanish, the main prize locally was dominance over the Dukedom of Milan in the possession of the Sforzas. Lake Como was of strategic value commercially and militarily since it provided the best means for transporting troops and goods to and from Milan. The lake’s transport links were vital for trade across the Alpine passes with Germany and beyond. Local commercial rivalries between cities like Como and Torno were exacerbated by rival military alliances with the French, Swiss or Spanish. The result was almost constant warfare between the major cities on the lake with each seeking to maintain a sufficient navy to protect its commercial interests and see off their rivals. These local navies would from time to time be supplemented by troops and ships provided by either the French or Spanish depending on to whom each town had pledged allegiance. These troops would also be supplemented by mercenaries mainly recruited from Germany or the Swiss Federation – the so-called Lanzichenecchi. These were in turn supplemented by kidnapped members of the local population and the bands of brigands and pirates who profited from the overall state of anarchy.

Condottieri

Federico de Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino in a portrait by Piero della Francesca. Federico had the bridge of his nose surgically removed to restore his field of vision once he had lost his right eye in battle.

Out of this environment of constant warfare and complex allegiances emerged the figure of the condottiere – a military leader able to command an army for hire usually serving one of the major powers but often themselves connected to a dukedom or granted the control of one or more of the major renaissance cities, For example, Alessandro Sforza was a condottiere in the early fifteenth century who, while serving the Papacy, was granted the Dukedom of Milan. Federico di Montefeltro was another condottiere who gained the Dukedom of Urbino. Other famous condottieri include Cesare Borgia who supplemented his role as a cardinal and son of the Pope by retaining under military power a massive principality in Central Italy in support of the Papal States.

Il Medeghino

Il Medeghino was such a condottiere who rose from his modest background as the son of a bankrupted debt collector to become the Marquis of Musso and Count of Lecco. He maintained an iron grip over both legs of Lake Como from 1523 to 1532. He was able to control almost all of the commercial and military traffic to and from Milan and the major routes over the Alps. He was one of the last of the great condottieri in the 16th century. But his career started off as a mere but brutal delinquent in the pay of the Dukedom of Milan as a hired assassin.

This view from within the Giardino del Merlo in what would have been inside Il Medeghino’s castle at Musso shows how he had vision of any of the Grisons’ ships descending from the Val Chiavenna or Valtellina.

As a mere delinquent, Il Medeghino killed his first victim at the age of sixteen. He fled Milan to avoid justice and joined up with one of the largest bands of pirates and kidnappers operating on Lake Como under the leadership of a Giovanni il Matto (Giovanni the Mad). Here he gained an early apprenticeship in how to exploit the anarchy arising from the continual conflicts between the French, the Spanish, the Swiss Federation and the Grisons. Giovanni il Matto was the son of Antonio il Matto. Antonio had established his base for piracy in Dongo, a town just beyond Musso on the western shore towards the top end of the lake. Pirates operated both from Dongo and Sala Comacina menacing commercial traffic on the lake and raiding lakeside towns to supplement their income by demanding ransoms for kidnapped prisoners. They were able to flourish by allying themselves whenever it suited with any one of the rival armies. Antonio il Matto was killed in September 1517 but piracy continued under his son, Giovanni who harassed the towns of the Tre Pievi for a further two years, aided by a still young Il Medeghino.

Note: The Tre Pievi was a semi-independent territory covering the top end of the lake with Gravedona, Dongo and Sorico in particular. It was established as a result of the Treaty of Constance in 1183 between Federico Barbarossa and the Lombardy League. It existed for a further 400 years.

Francesco II Sforza, the Duke of Milan and the last in the Sforza line.

In 1521, Giovanni il Matto was appointed Prefect of Lake Como by Francesco Sforza, the Duke of Milan, who then commanded him to take over control of the city of Como. Como was allied to the French whilst the Duchy of Milan was allied to the Spanish. Giovanni led his fleet of pirates incorporating some German mercenaries provided by Sforza to land in Borgo Vico. Here he waited in the hope that the Rusca faction (anti-French) within the city might aid his assault. However the French Governor repulsed Giovanni and his pirates with his own mixed army of Swiss mercenaries, Lombardy bandits and a few Como residents. Giovanni was captured and beheaded along with his brother in Griante just north of Cadenabbia on the westerns shores of the lake.

Il Medeghino had learnt a lot from these early years of apprenticeship both in terms of military strategy and political acumen. He re-allied himself with the Sforzas who, in 1524, granted him the Signoria of Musso in perpetuity. It is suggested that he tricked his way into gaining control of Musso by substituting the sealed letter from Sforza which he had been entrusted to deliver to the castle’s governor. In any event, he quickly set to optimising the defences of the castle and its port and building up his fleet of ships. When also granted the Signoria of Lecco, he had control of both legs of the lake and, as importantly, access to the outlet of the River Adda which provided a navigable link towards Milan. He took on the French and the Grisons causing them to retreat back up the Valtellina and the Val Chiavenna. As his power and control of his territory increased, he became increasingly independent of any of the major powers. At one stage, with the Grisons seeking peace with Milan, he even captured their ambassadors on their return from peace negotiations and held them to ransom.

Fresco in the Castello Medicea in Melegnano depicting a Grisons attack on Il Medeghino’s Castle of Musso.

By 1525, Il Medeghino had become an out and out pirate freely operating from Musso in capturing ships, seizing their merchandise, imprisoning their passengers whether fellow nationals or foreigners and putting their freedom up for ransom. He rebuilt the tower at Olonio with its command over the mouths of the Val Chiavenna and Valtellina and extracted duty on all goods that passed. He extracted the price of 500 gold ducats (scudi) from the Grisons just to grant them a licence to trade. As an example of his ransom income, he is said to have obtained 4,000 gold ‘scudi’ as a ransom for a noble Milanese called Girolamo da Carcano. (An average yearly income at the time has been estimated as from about 10 to 15 scudi).

The First Musso War

Looking south from the Castle of Musso, Il Medghino would have had ample warning of any ships coming up from Como or Lecco.

When the Spanish attacked his castle and port in Musso, Il Medeghino put a blockade on Como causing many of its citizens to flee to Mendrisio or Lugano. He also blocked all traffic at Lecco. The Spanish were forced into peace negotiations which were finalised at the Treaty of Pioltello on the 31st of March 1528. Under the terms of this treaty il Medeghino was granted total control of the lake except for a 10 mile zone around Como, but including Menaggio, the Tre Pievi, Valsassina, and Lecco as far down as the bridge across the Adda. Inland he was granted control of the Valmadrera, Vallassina, and the castle of Monguzzo. On Lake Lugano he was given Osteno and Porlezza. In exchange he promised to allow merchants free access across all his territories as previously granted to the Grisons. Il Medeghino now dealt directly with the Spanish Holy Roman Empire without reference to their other ally, Francesco II Sforza and the Dukedom of Milan. The castle in Monguzzo became his own personal prison and, perhaps to reflect the commercial value of his Musso empire, he now coined his own currency. He himself became the entirely independent Marquis of Musso and Count of Lecco.

The shaded areas show the territory under Il Medeghino’s control following the Treaty of Pioltello.

But all good things come to an end, and Il Medeghino’s fortunes changed following the Treaty of Cambrai on August 3rd 1529. This treaty temporarily ended war between France and the Holy Roman Empire and, as a result, confirmed Spanish control over the Sforza’s Duchy of Milan. Charles V, the Spanish king, now wanted to return Il Medeghino’s fortress at Musso into Sforza hands. Il Medeghino did not accept this and resisted all attempts by the Milanese to seize control over his dominion over Lake Como. The pressure from the Sforzas built up even further following their signing of an alliance with the Grisons and the Swiss Federation in March 1531.

The five ranks of rowers in a quinquereme following a Roman design.

Together they dismantled Il Medeghino’s tower at Olonio with him having been branded a rebel by the Sforzas. His response was to set out building up his troops and his navy ravishing the lakeside towns to gather in food and capture men to row his growing fleet. He now had twenty two boats in his fleet but supplemented these by building some additional quinquereme ships based on the Roman design with their five levels of rowers. He did not wait to be attacked by the fleet being put together by the Sforzas in Como but went immediately on the offensive.

The Second Musso War

As Il Medeghino’s relationship with Francesco II Sforza worsened, so did that with the Grisons. Partially this was due to the Grisons adopting protestantism in 1525 and Il Medeghino’s previous military support alongside his brother, the future Pope Pius IV, to the catholic cantons within the Swiss Federation. But the murder of the Grison’s ambassador Martino Bovellini, captured by Il Medeghino’s men in Cantù on 3rd March 1531 on his return from Milan, hastened the conflict. This provocation was swiftly followed by Il Medeghino’s attack up the Valtellina with a force of mercenaries and Spanish soldiers left without employment following the Treaty of Cambrai. Il Medeghino won a conclusive victory against the Grisons at Morbegno in the Valtellina on the 23rd march 1531. The Grisons lost between 300 to 500 men at the cost of a mere couple of Il Medeghino’s soldiers.

Another of Il Medeghino’s naval battles off the coast of Bellagio and Varenna, in the Castello Medicea at Melegnano.

The protestant forces in the Swiss cantons and the Grisons, with some assistance from the Spanish in preventing Il Medeghino from replenishing his supply of mercenaries, replied by attacking and seizing Porlezza. They were prepared to assist Francesco II Sforza on the condition that the Duchy ceded all claims to the Val Chiavenna and the Valtellina to the Grisons. The Duchy then took to the offensive against Il Medeghino’s castle in Monguzzo.

‘Lanzichenecchi were Swiss mercenaries employed by all sides in the Renaissance conflicts. While the Spanish did not intervene directly in the Second Musso War, they did prevent Il Medeghino refreshing his numbers of mercenaries from Switzerland.

While the war on land was not going well for Il Medeghino, he had more success on water. His fleet continued to outmanoeuvre that of the Duchy of Milan. The Swiss fleet, attempting to blockade Musso, also suffered losses from a series of successful sorties. The Grisons and the Duchy then tried to seize control of Lecco and break Il Medeghino’s links between that city and his base in Musso. Over the two days of the naval battle of Lecco, Il Medeghino captured the Duchy’s colonel, Alessandro Gonzaga and caused Gonzaga’s 1200 soldiers to flee. The following day he forced the retreat of the entire Grisons contingent while fighting with a mere 100 men.

But his luck did not hold out when on 13th February 1532, his brother Giovanni Angelo de’Medici, the future pope Pius IV, was captured. To secure his brother’s release, Il Medeghino entered negotiations with Francesco II Sforza.

From Marquis of Musso to Marquis of Melegnano

Il Medeghino negotiated an honourable and favourable peace with Milan. He agreed to cede all his territory on and around Lake Como including his castle in Musso. In exchange he was made the Marquis of Melegnano, a small town to the south east of Milan. He was also awarded the sum of 35,000 scudi and an annual income for life of 1000 scudi and a total amnesty from any legal action against either himself or his followers. The Swiss destroyed the castle at Musso and extracted a promise from Francesco Sforza that the Milanese would never re-occupy or rebuild it.

The Castello Mediceo in Melegnano

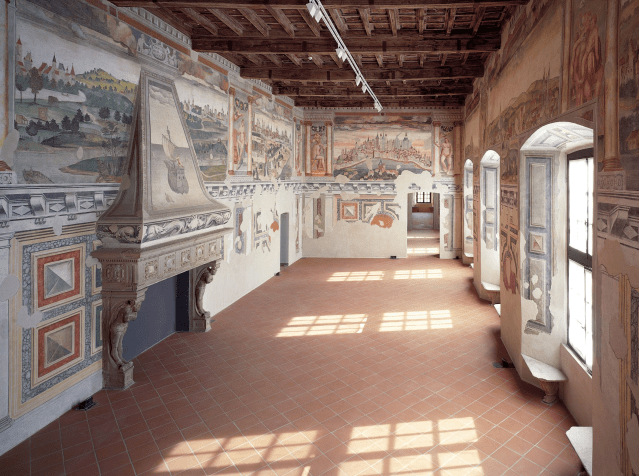

Il Medeghino occupied the castle in Melegnano, now known as Castello Medicea, and commissioned its redecoration with a series of frescoes that included scenes from some of his famous battles such as those of Musso and Lecco.

The frescoes in the Castello Mediceo have been recently restored.

Il Medeghino continued his career in Piedmont for a number of years as one of the most successful condottiere of the 16th century. His sister Margherita married Count Gilberto Borromeo and she had a son who went on to become the sanctified Cardinal Carlo Borromeo. His cousin Gabrio Serbelloni was ennobled and his brother went on to become Pope. It was this brother who commissioned a massive sepulchre designed by Leone Leoni in Milan’s cathedral for Il Medeghino on his death in 1555. Conversely Francesco II Sforza had died much earlier in 1535 without heirs and so brought to a close the era of the Milanese Sforzas.

The tomb of Gian Giacomo de Medici ‘Il Medeghino’ in Milan’s Duomo. The sepulchre was commissioned by Il Medeghino’s brother, Pope Pius IV and designed by Leone Leoni.

Further Information

At Musso, the Museo di Musso contains a model reconstructing the castle as developed by Il Medeghino. The grounds of his castle have now been converted into a botanical park called the Giardino del Merlo. There is also an agriturismo named Il Medeghino on the road up towards the Chiesa Sant Eufemia. There is even a boat hire company calling itself Il Medeghino but based in Como. It and many other boat hire companies are listed at Boat Hire and Water Taxis

The Church of Saint Eufemia in the grounds of the old Castle of Musso

At Dongo, I can highly recommend the Museo della Fine della Guerra relating the last days of the war and the historic events that occurred in Dongo at the time including the capture of Mussolini and the execution of the fascist leaders on the Dongo lakefront. The audio commentary is available in a variety of languages and includes some fascinating first hand accounts of those last days by some of the participating local residents and partisans including Michele Morandi (nome di guerra ‘Bill’) who personally arrested Mussolini and is also said to have participated in Il Duce’s execution in Mezzegra.

In Melegnano, the Castello Medicea, with its renovated series of frescoes depicting il Medeghino’s famous battles, is now run by FAI with opening times on Saturdays and Sundays from 10.00 till 18.00.

One of the coins issued by Il Medeghino from the Musso mint.