The logo of the Progetto San Francesco, part of the Centro Studi Sociali Contro Le Mafie, uses the metaphor of an octopus appropriately to suggest the many ways in which the mafia insinuate themselves within the fabric of society. The gun is less relevant for the new variant of financial crime infecting our area, but it still sits within their armoury.

Organised crime is like a virus whose bacteria spread across society breaking out from time to time in various hotspots, mutating along the way to evade the best efforts of law enforcers. The mafia have learnt to avoid attracting attention through their past acts of violence and intimidation. Instead their disease is more likely to attract attention these days once hotspots become self-evident or new variants are uncovered. Such is the case here in Como following the declared bankruptcy and closure of one of the most popular local restaurants – Pane e Tulipani, in the heart of the old city in Via Lambertenghi. Links soon appeared between this bankruptcy and the arrest of 34 people in the Province of Como and Calabria in an anti-mafia investigation codenamed ‘Nuovo Mondo’.

The now vacant site of ‘Pane e Tulipani’, formally one of the most popular and fashionable of Como’s restaurants in the old town.

Although the quality of the food and service had deteriorated of late at Pane e Tulipani, it still came as a surprise when the restaurant declared itself bankrupt on the 18th October 2018. Suspicions that all was not as it should be were confirmed four days later when the Guardia di Finanza intercepted a couple of Tunisians in a car close to the restaurant without a permit to enter the old city. In full view on the passenger seat of their car was a box containing financial documents belonging to the restaurant. The Tunisians had been instructed by the restaurant’s accountant, Alberto Caremi, to pick up and destroy incriminating financial documents relevant to the restaurant’s bankruptcy. What these documents and subsequent illegal attempts to sell off company assets revealed was a clear case of fraudulent bankruptcy. Company partners and accountants for Pane e Tulipani were immediately arrested.

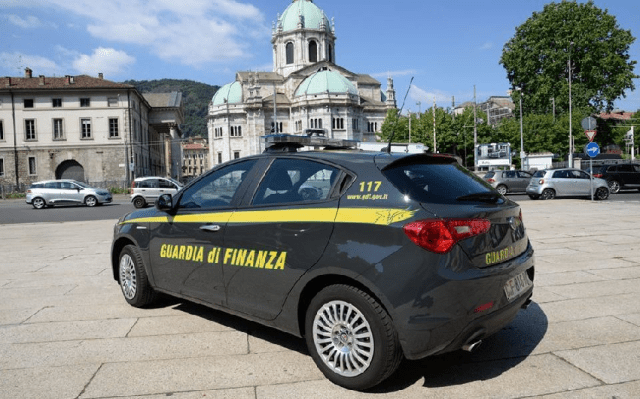

The Guardia di Finanza (financial police) led the inquiries into the bankruptcy of Pane e Tulipani and the other companies registered in the Province of Como and the Calabrian city of Gioia Tauro which were deliberately forced into bankruptcy.

Pane e Tulipani – The Scam

Subsequent investigations revealed an elaborate scam to cheat the tax authorities and make money out of a fraudulent bankruptcy. The scam worked by creating two companies linked to each other with one, Pane e Tulipani itself, responsible for running the restaurant and for all associated costs, and the other, Napo Srl, which took out a mortgage to purchase the restaurant’s premises. Although both companies were owned by exactly the same partners, Napo set out to bleed Pane e Tulipani dry by charging it €13,000 a month for rent. This left the restaurant unable to pay its tax bills leading eventually, inevitably and deliberately to bankruptcy. The partners then hoped to conclude the scam by selling the property in 2019 thus paying off the mortgage, freeing them of the guarantees provided to cover that mortgage and leaving them with a good profit from the sale unhindered, due to bankruptcy, of having to pay the creditors of the restaurant including the tax authorities.

Acsm Agam is a utilities company part owned by the Comunes of Como, Varese, Sondrio and Monza

The mastermind and chief architect of this scam was Paolo Lanzara, a 51 year old accountant from Como who also happened to be on the board of the utilities company Acsm Agam, representing the interests of the Comune di Como as part owners who had sponsored that appointment. (His association with Acsm Agam resulted in further embarrassment to the current mayor of Como, Mario Landriscina, when it was revealed that Lanzara had failed to mention his previous arrest in 2018 when the mayor first sponsored his appointment.)

Also involved in the scam was another Como financial professional, Bruno De Benedetto – a person behind a host of businesses in and around Como either as a partner, financial advisor or the real power behind a series of figurehead directors. De Benedetto had been working with Lanzara in attempting illegally to sell off the bankrupt company’s assets and also to purchase the physical premises of the restaurant.

Bruno De Benedetto – Villain and Victim?

Bruno De Benedetto is no saint. He was the ‘trusted’ financial advisor to Massimiliano Ficarra, an accountant with residence in Gioia Tauro in Calabria but domiciled in Lomazzo in the Province of Como. Ficarra is a mafioso – a member of the Cosca Piromalli, one of the largest of Calabria’s ‘ndrangheta clans operating not just there but in Lombardy and other European cities. Ficarra is at the heart of the Nuovo Mondo investigation and is now facing a 12 year prison sentence.

The restaurant on the lakefront in Villa Olmo’s gardens, owned by the Comune di Como who grant license for its management following public auction.

De Benedetto’s personal stake in restaurants in and around Como is extensive and tumultuous. In addition to the illegalities associated with the failure of ‘Pane e Tulipani’ he is also accused of falsely applying to manage the Lido in Villa Olmo with its bar and the adjoining restaurant. His company, Villa Olmo Lago, had previously run the restaurant attached to the lido for the previous ten years but in 2019 it was forced into bankruptcy left owing €500,000 in unpaid taxes.

The bar and lido in the gardens of Villa Olmo now managed by a company granted license by the owners, the Comune di Como following public auction. The current managers are not associated with Bruno De Benedetto or implicated in any way in the Nuovo Mondo investigation.

The Comune di Como own a number of businesses around the city which they license others to manage in response to public competition. In recent years it would appear that many of these license competitions have not run smoothly, for example the lido in Viale Geno has remained closed now for two years since all applicants so far have failed to meet the competition’s criteria. When the Comune published the competition for licenses to run the Lido in Villa Olmo and the adjoining restaurant, De Benedetto applied either directly or through frontmen. However, as a result of the Nuovo Mondo investigation and the previous bankruptcy of De Benedetto’s Villa Olmo Lago – his company that had previously managed the restaurant for 10 years – it became clear that De Benedetto’s new application to manage both restaurant and lido was illegal. It is an offence to participate in a competition for public contracts if you lack the relevant means, skill or experience – a measure no doubt put into law to avoid cronyism. De Benedetto was held in Como’s prison, Bassone, on these additional charges of ‘turbativa d’asta’ in addition to the charges relating to the forced bankruptcy of ‘Pane e Tulipani’.

Recent competitions for licenses to manage some of the Comune di Como’s properties have been fraught with difficulties and delays with the lido on Viale Geno remaining closed for the last two tourist seasons resulting in loss of revenue to the Comune and loss of facilities to residents and visitors alike.

De Benedetto’s companies do not like paying taxes. Even his boutique hotel ‘The Avenue’ in Piazzolo Terragni was accused at the start of the year of not handing over €40,000 due to the Comune and representing the city tax levied on all hotel guests. This represents a non payment over a four year period which it appears the Comune themselves never took active steps to recover. That lack of concern and other possible irregularities are now being looked at more closely prior to the case coming to court later this Spring.

The Avenue Hotel in Piazzolo Terragni, accused of allegedly not handing over the city tax charged on all overnight guests.

Usury

Faced with the ever increasing number of charges against him with the revelations of his connections to organised crime, De Benedetto has decided to present himself as a victim. He has denounced three local financial professionals with usury claiming he borrowed a total of €1 million to cover his debts to tax authorities for which he had to pay back €1.6 million. The annual rate of interest on these loans ranged from 80 to 600%, far exceeding the legal limit of 21% beyond which a loan is deemed as usurious. Two of the accused – Gabro Panfili, 74 years old and resident in a lakeside villa in Laglio and Paolo Barrasso, 59 years old and resident in Como – have previous convictions for usury and so have been imprisoned awaiting trial. The third, Giovanni Gregorio, 82 years old and resident in Bellagio, is under house arrest. De Benedetto is also claiming that Gregorio issued his loans under the condition that De Benedetto put a Nigerian woman on the books of those employed at the Avenue Hotel, so that she would then be able to obtain a residency permit. Her wages of around €54,000 a year would then be paid directly to Gregorio. We do not know if the woman was asked to pay Gregorio for this favour.

Organised Crime

The mafia activities in the Province of Como revealed in the Nuovo Mondo investigation are linked to companies and people from Gioia Tauro in Calabria, the site of Italy’s largest container port. This is also the base of the Piromalli ‘ndrangheta clan.

We now move our focus away from Como further south to the comunes of Lomazzo, Fino Mornasco, Cermenate and Cantù where links between local businesses and the ‘ndrangheta have been known to exist for some time. They have been charged for drug trafficking and the corruption of local officials in order to obtain favourable contracts – as well as the gradual infiltration into some specific industrial sectors such as building and waste management. The extent of their influence can be gauged by the daytime execution in 2008 of Franco Mancuso in a bar in Cadorago in front of witnesses who remained silent. Mancuso had publicly ‘dissed’ Bartolomeo Iaconis of Fino Mornasco – the local ‘ndrangheta boss attached to the Piromalli family. That killing was intended to underline the message that the area around Lomazzo was mafia territory.

Young people express their revulsion of organised crime at an antimafia demonstration in Como

The ‘ndrangheta have always favoured establishing themselves in the smaller towns around the Milanese hinterland where it is relatively easier to corrupt local public administrations, as in the case of Lomazzo. Here Marino Carugati, 77 years old, was mayor in 1987 and was subsequently linked to the ‘ndrangheta. Carugati’s colourful past includes having to call upon the help of national politicians in 2008 to get him out of solitary confinement in Eritrea where he had been imprisoned under the accusation of supplying faulty wood working machinery to his Eritrean partner. More recently in October 2019 he and 33 others in and around Lomazzo and in Calabria were arrested as a result of the lengthy ‘Nuovo Mondo’ investigation.

Nuovo Mondo – the ‘New World’

Why a new world – because, thanks to the two major architects of a new scam operating since 2010, the mafia had developed a novel form of white collar financial crime which allowed them to stay back in the shadows. No guns or intimidation were needed, just wily accountants and an army of dupes prepared to act as figureheads for bogus companies. The major, but not the only victim of this crime, was the state due to lost tax revenue. The major beneficiary was the ‘ndrangheta who could use the false companies to launder money from their other illicit activities and redirect their untaxed profits into further infiltration and corruption of local business and public administration.

Why a new world – because, thanks to the two major architects of a new scam operating since 2010, the mafia had developed a novel form of white collar financial crime which allowed them to stay back in the shadows. No guns or intimidation were needed, just wily accountants and an army of dupes prepared to act as figureheads for bogus companies. The major, but not the only victim of this crime, was the state due to lost tax revenue. The major beneficiary was the ‘ndrangheta who could use the false companies to launder money from their other illicit activities and redirect their untaxed profits into further infiltration and corruption of local business and public administration.

The two architects of the scheme were Massimiliano Ficarra, an accountant resident in Gioia Tauro in Calabria and Lomazzo and a banker from Milan, Cesare Pravisano also resident in Lomazzo. Their scheme was similar to that of Pane e Tulipani in that it played on the relationship between two separate legal entities, namely a cooperative of industrial workers and a consortium. As with Pane e Tulipani, the scam works by pairing an ‘active’ company with a ‘passive’ one in which the active entity undertakes the physical activity and incurs all related costs. It is then deliberately set on a course to bankruptcy. Meanwhile the ‘passive’ partner retains a semblance of legality while profiting from extracting all value from its ‘active’ member to which it appears to be entirely independent. The relationships are complex but this is how I have best been able to understand how it worked. The consortium, on gaining a public or private contract, would sub-contract the work to the cooperative.

- The work cooperatives were headed up by figureheads but were actually controlled by the consortia who remained separate legal entities.

- The cooperatives took advantage of their legal status to delay payment of taxes and insurance contributions for their workers who should in any case have been treated as partners.

- The cooperatives provided the workforce and other services under subcontract to the consortia who could then expense these charges for services which consisted mainly of manpower and included the percentage for VAT which the cooperatives should then have passed on to the state.

- The consortia avoided any direct employment of workers and so had no liability for insurance contributions.

- The profits of the consortia were reduced on paper by the cooperatives issuing false invoices whose payment went directly to the fraud originators.

- The cooperatives deliberately failed to make the necessary tax returns or the due payments of VAT and so, claiming they were unable to do so, declared themselves bankrupt. Bankruptcy would typically follow after two years of operation.

- The fraudsters then created a new cooperative with exactly the same partners and employees of those made deliberately bankrupt. Employees of these cooperatives would remain entirely ignorant of the fact that they were now working for a new legal entity.

- The consortia would remain entirely within the law with the correct payment of taxes but on profits massively reduced by the false invoices issued by the now defunct cooperative.

From 2010 until 2019 it is alleged that 40 cooperatives had been set up with the deliberate purpose of driving them into bankruptcy. 34 people were arrested for involvement in this scam including the two main architects, the figureheads for the cooperatives and the related consortia and others such as Bruno de Benedetto for his attempt to derail the contracts for the management of the lido and restaurant in Como’s Villa Olmo.

The charges brought against them were for:

- Causing deliberate bankruptcy

- Issuing false company accounts

- Issuing fake invoices

- Disrupting public contracts.

A Victimless Crime?

Certainly white collar crime does not result directly in victims like Franco Mancuso in 2008 at Carugo but the impact goes way beyond losses to the state’s tax coffers which in this case were immense. The other main losers are all those legitimate businesses who lost out in their bids for public and private contracts in favour of the mafia’s consortia. The mafia had been able to undercut them since the lower bids had no need to reflect the actual costs of delivering the required services. Additionally all the employees of these cooperatives were victims. They not only lacked what should have been the benefits of participation in a working cooperative but were treated as mere employees exploited by lack of national insurance cover and without contributions made to their eventual pension entitlement. The physical environment also suffered through entrusting works to businesses totally prepared to ignore regulations governing the management and transportation of waste and other forms of environmental control.

Pane e Tulipani’s terrace on the corner of Via Tatti now shows degradation resulting from its mafia association.

The beauty of the scam for the mafia was that they were able to stay in the background, casting their shadow undoubtedly but sheltering behind the facade of one or two known associates. But this description of one of the scam’s chief architects, Massimiliano Ficarra by the Como Carabinieri should leave us in no doubt as to whether the mafia were behind the scam:

«Massimiliano Ficarra is a dependable and ubiquitous accountant, at the service of various criminal families of accredited ‘Ndrangheta membership. It is immediately obvious that he is constantly used to maneuvering in those environments. He is one of the principal members involved in organized and effective money laundering activity, with particular attention to the reuse, in economic activities, of the money coming from the Molè Piromalli mafia association “.

Conclusion

Bruno De Benedetto was Ficarra’s financial professional ‘of trust’. De Benedetto partnered with Paolo Lanzara in masterminding the Pane e Tulipani bankruptcy. Paolo Lanzara was the Comune of Como’s representative on the board of the utilities company Acsm Agam. Another of Ficarra’s co-defendants, Alessandro Tagliente, resident in Appiano Gentile, was the right hand man of ‘ndrangheta boss Bartolomeo Iaconis, convicted for ordering the murder of Franco Mancuso. The mafia, with this new variant of their particular disease, have certainly cast a deep shadow over the city and Province of Como.

Between June and November 2020 sentences have been passed down on many of the Nuovo Mondo defendants including 12 years imprisonment for Ficarra and 11 for Pravisano. No doubt much more will emerge in coming months including further detail of De Benedetto’s activities and his accusations of usury. In the meantime Como is in the grip of another financial scandal involving some local businessmen and their accountants accused of avoiding tax in exchange for illicit cash payments (tangenti) to senior officials in the city’s tax office – the Ufficio Entrate. But that is another story for the near future!