Noir in Festival this year takes Batman as one of it main themes.

This Friday, 6th December, sees the start of the Como-based section of ‘Noir in Festival’ – an annual feast of crime film and fiction. This celebration of the ‘noir’ genre is into its 29th edition and its the fourth year that Como has co-hosted this festival alongside Milan. Two awards for literature are made or presented during the course of the festival and two for film. Additionally there are interviews with authors and screenings of films in original language as well as opportunities for media-folk to get together. The Como-based events, all of which are free, are held on Friday and Saturday in Villa Olmo. Events continue from Sunday onwards in Milan. The Como events in English are posted on CC’s Calendar but the full programme is available from the festival’s website.

The Como-based events for this year’s festival are held over Friday and Saturday 6th/7th December in Villa Olmo. Entrance is free.

Glorious Prizes

Jonathan Lethem

For literature the winner of the internationally renowned Raymond Chandler Award this year is the American writer Jonathan Lethem. Last year’s winner was Jo Nesbo and in 2017, Margaret Atwood. Jonathan Lethem will be presented with the award on Saturday evening at 21.00 in Villa Olmo. There is also a prize for Italian novelists named after the ‘father’ of Italian noir, Giorgio Scerbanenco.

For film an award is made for the best international film selected out of the six entered for the competition and screened during the festival. This year there are films entered from South America, China, Sweden and USA. The ‘Premio Caligari’ is a prize awarded during the festival to nationally-made ‘noir’. This prize is promoted by IULM (The Free University of Language and Communication at Milan) and so most of these films are screened on their site during the Milan-based part of the festival. However, the mood of the festival is set by a showing on Friday evening at 16.00 in Villa Olmo of Carol Reed’s atmospheric spy story ‘The Third Man’ starring Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles.

A still from Carol Reed’s ‘The Third Man’ set in bomb damaged Vienna

The whole mix of special events, film screenings and conversations with authors goes to form an intriguing dive into this most atmospheric of literary and visual genres. Margaret Atwood’s acceptance speech on receiving the Raymond Chandler Award here in Como two years ago, is worth quoting in part for its insight into why the genre remains so appealing:

Margaret Atwood, Raymond Chandler Prize, 2017

‘….I am not a crime writer as such – just a writer about human behavior, which includes crimes among all of its other manifestations. Why are we fascinated by such acts? Because we would never do them ourselves, or because we fear we might? In our dreams and nightmares we find ourselves engaged in the most bizarre activities – perhaps that is what crime writing is for us – an exploration of our nightmares. And what lies between us and this nightmare world? Only the thinnest of barriers.’

The Noir genre may have originated with Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett in the USA alongside Hollywood but it seems now to be a truly international genre. Yet there seem to be some geographical hot spots where ‘noir’ is at its densest. One of these hot spots has to be Italy with strong representation in both film, TV and literature created by a host of writers. Events in Italy’s recent history have almost made ‘noir’ an involuntary response within a society that has suffered so many moral and emotional traumas through the ‘anni di piombo’ when from 1969 to 1980 there were over 4,200 terrorist incidents. Whilst Italy did face open civil war from 1943 to 1945, these ‘years of lead’ in the 70s and 80s have also been described as a form of creeping civil war with atrocities born out of the shadows and formed out of duplicity, deceit and ambiguity – actions performed by a ‘dark’ state intent on spreading fear, tension and anxiety, a true ‘nightmare world’ to recall Margaret Atwood.. What could be more designed for ‘noir’ than a parallel state apparatus incorporating parts of the army and secret services set upon exploiting political extremists in creating a so-called ‘strategy of tension’? Remarkable but true – this was Italy at the height of the Cold War.

A Series of Anniversaries

12 December will be the 50th anniversary of the terrorist attack in Piazza Fontana, Milan.

70 years ago, Carol Reed’s ‘The Third Man’ was awarded the Grand Prix at Cannes on its release in 1949. The brilliance of that film, with its atmosphere of menace and secrecy located on the front line of a Cold War first emerging from the bomb-damaged cities of eastern Europe, shares inspirational space with Batman at this year’s Noir Festival. Also 70 years ago, NATO was established to coordinate western power responses to the perceived internal or external threats of communism. Fifty years ago on 12 December 1969, a bomb exploded in Piazza Fontana in Milan killing 18 people and injuring a further 84. That outrage, along with a number of bomb explosions in Rome on the same day, saw the opening salvo in Italy’s parallel state’s Strategy of Tension – known as ‘stragismo’. In response to the growing popularity of the Communist party in Italy and the wave of radicalism across Western Europe, ‘rogue’ elements of the right-wing establishment sought to discredit the left and provoke a reactionary response to terrorist atrocities they themselves committed. There is speculation that the Italian secret services, whose direct involvement in terrorism has been established in the courts, kept both NATO and the CIA informed of their actions.

The ‘Nightmare World’ of Cold War Italy

Judge Salvini has spent a good part of his judicial career in trying to establish the facts behind the ‘Strategy of Tension’.

It took from 1969 to 2005 for the Italian judiciary to finally close its process on the bombing of the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in Milan’s Piazza Fontana. By that time, although guilt had been established, no further sentencing was possible due to the passing of time under the statute of limitations. The fault for this does not lie with the judiciary, but rather is down to the success of the ‘occult’ powers committed to frustrating the work of the magistrates and courts through a process known as ‘depistaggio’ – misleading and derailing investigations through witness interference often resulting in verdicts of ‘not proven’ which, as in Scottish law, is not the same as ‘not guilty’

The Strategy of Tension

The strategy of tension ran like this. Commit acts of terrorism which appear to be perpetrated by the extreme left. Find an ostensible culprit amongst the left and pressure the magistrates to arrest them. Use neo-fascist extremist gangs to undertake the acts of terror. Use the ‘parallel state’ consisting of parts of the army and the carabinieri along with the secret services to obfuscate justice if right wingers are accused. Exploit the rising levels of alarm in the general public to get increased popularity for an authoritarian anti-communist government or foster acceptance of a right-wing coup d’etat. Extraordinary though this may seem, this is exactly how the Cold War was conducted in Italy backed up by the numerous establishment members of the illegal and fiercely anti-communist P2 masonic lodge.

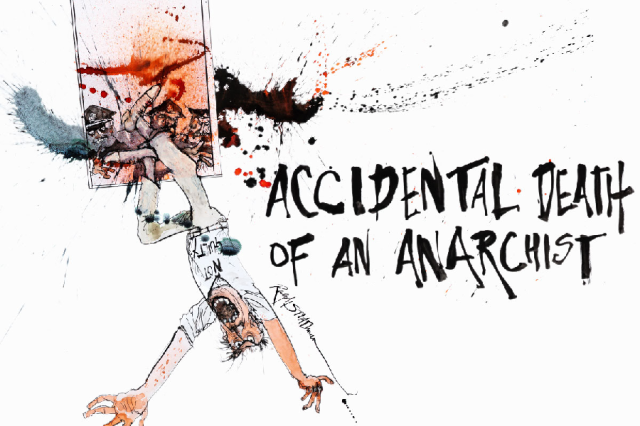

Dario Fo wrote the play ‘The Accidental Death of an Anarchist’ following the alleged suicide of one of the two anarchists initially arrested for the bombing in Piazza Fontana. The anarchist, Giuseppe Pinelli, died falling out of a top floor window at Milan’s police hesadquarters.

The players in this strategy divided into either operational or directional groups. The operational groups were those extra-parliamentary groups of neo-fascists such as Ordine Nuovo strong in Northern Italy and Avanguardia Nazionale with its support more focussed in the south. They undertook the assassinations and bombings. The directional groups were responsible for the overall policy and for providing protection to the operational elements by delaying and misleading the judicial enquiries through a variety of means. The directional groups consisted of SID (the name of the secret service at the time), elements of the army and some elements of the Carabinieri. It is debatable to what extent the directional groups managed to control their operational partners. It is also unclear to what extent the parallel state structure of the directional groups operated with the knowledge of the established state given that both ‘states’ shared membership in the illegal conspiratorial P2 masonic lodge.

Massimo Carlotto

If all this sounds fanciful, consider the direct experience of ‘noir’ writer Massimo Carlotto, author of ‘Death’s Dark Abyss’ (2004). Massimo Carlotto was a student member of one of the left wing extra-parliamentary groups ‘Lotta Continua’ (Continual Fight). He was accused when 19 of murdering a 24 year old female student in Padova. Condemned to a 16 year prison sentence and on the advice of his lawyers, he fled to France to take shelter under President Mitterrand’s refusal at the time to extradite left-wing political prisoners back to Italy. He subsequently moved on to Mexico but was then later expelled and faced re-imprisonment on his return to Milan. There then followed a 17 year fight for his liberty making his one of the longest campaigns in recent history leading eventually to his release granted through a presidential pardon from Oscar Luigi Scalfaro in 1993. However it was not until 2004 that he finally regained all his civil rights with the courts granting full exoneration of any responsibility for the original crime. With his direct experience as a victim of ‘stragismo’ it is hardly surprising that Carlotto is perhaps one of the bleakest of the current generation of Italian noir authors. Massimo Carlotto had inadvertently breached that thinnest of barriers separating us from nightmare.

Fact Stranger than Fiction

The machinations of Italy’s ‘dark state’ with its cynical readiness at the time to sacrifice its own citizens in order to deliberately raise tension and anxiety within the population at large defies credibility. It also challenges writers of ‘noir’ since fact (doggedly achieved by the heroic dedication of many of the Italian judiciary) has so often exceeded what might form credible fiction.

Giancarlo de Cataldo

The novels of Giancarlo De Cataldo represent one response to this. In his ‘Romanzo Criminale’ De Cataldo uses his in-depth knowledge as a magistrate in Rome to depict the lives of the common criminals who formed the notorious Banda della Magliana in the late 70’s. These partially cover the procedural aspects of judicial enquiries but Margaret Atwood would appreciate that the main focus is on the characterisation of this group of petty criminals. This novel shares similarities with Marlon James’s ‘A Brief History of Seven Killings’ which also explores the lives of petty criminals caught up as foot soldiers in an orchestrated attempt at political and social destabilisation at the same period but within another bitter theatre of the Cold War – Central America, the Caribbean and Michael Manley’s Jamaica in particular. Giancarlo De Cataldo’s follow up to ‘Romanzo Criminale’ was ‘Nelle Mani Giusti’ which covers the period of the assassinations of the Palermo magistrates Falcone and Borsellino and the end of the First Republic resulting from the political corruption trials in Milan known as ‘Mani Pulite’. He will be at the festival at 19.00 on Saturday 7th to discuss his latest crime novel ‘Quasi per Caso’ which is set in the mid nineteenth century in Piedmont at the time of the struggle for independence from the Austrian Empire.

ITALY COMES IN FROM THE COLD?

Following on from the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the ‘Mani Pulite’ trials in Milan in the 1990s caused the collapse of the so-called First Republic and marked the end of the Cold War in Italy. Historians have still to disentangle the full scope and impact of the Cold War here but, due to the deep and long-lasting political divisions in the country, some historians have characterised the period as representing a sustained form of creeping civil war running on uninterrupted through the ‘anni di piombo’ and following on from the open civil war fermented by the Nazi Occupation after the Armistice in September 1943. Some suggest that such deep divisions along such polarised political lines require a form of ‘Truth and Reconciliation’ process similar to that conducted in South Africa after the collapse of Apartheid. No doubt the country and its political structures would be strengthened by this but cupboards are still so jammed full of skeletons for this to prove unlikely to happen. And so, Italian ‘noir’ will thrive for the foreseeable future, and we here in Como will at least be able to continue to take pleasure in ‘Noir in Festival’ which must be the only positive but bitter-sweet by-product of such tempestuous times.

Further Reading

The following form the nucleus of the current group of Italian noir authors:

Giancarlo de Cataldo,

Gianrico Carofiglio,

Maurizio De Giovanni,

Donato Carrisi,

Maurizio Carlotto.

English editions are available for some of the books by all of the above authors.

To understand more about Italy’s ‘anni di piombo’, I would recommend:

Leonardo Sciascia: ‘The Moro Affair’

Anna Cento Bull (University of Bath): ‘Italian Neofascism – The Strategy of Tension and the Politics of Nonreconciliation.’

Como Companion has previously written about ‘Noir in Festival’ and Italian crime writing in Noir 2018: Moral Ambiguity and Death