Paul Wright and his wife Nicola moved from England to Lake Como over thirty years ago. They have faced various challenges and tribulations over this time but have never regretted making that move. Initially they tested the waters by house sitting a friend’s home in Moltrasio and, once they found their venture to be economically viable, went for full expatriate immersion by selling up their home in Surrey in favour of a villa in Argegno. Paul recorded the couple’s experiences as expatriates in a trilogy of books available on Amazon.

I read the first two titles in the trilogy fascinated to learn how he and his wife responded to the challenge of moving to a different country and what it was about Italy that they found so appealing, and at times, exasperating. I could not help contrasting his views and experiences with those of my own since my wife and I also moved to Italy at around the same time.

The Expatriate Genre

My wife and I first moved to Italy in 1988 while Paul and Nicola moved to Moltrasio from Surrey in 1991. Increasing numbers of people at that time were exploring the possibilities of living abroad within the European Union, a right that was not actually established in law until the signing of the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. A genre of biographical nonfiction developed on the back of this interest in which the authors recounted their experiences of setting out to establish themselves in a foreign land. The most successful of these was Peter Mayle’s ‘A Year in Provence’(1991). It set in chain this fashion for accounts of foreigners (usually from the cold and wet North) settling in envious sunny rustic environments. I hated Peter Mayle’s book with an almost irrational vehemence. The major irritant for me was the author’s air of self-satisfied smugness that lay behind the rose-tinted cliche-ridden depiction of what had to be a pseudo-reality. It was a journalist’s time-limited project whose principal aim from the start was the production of a best seller. Unfortunately its immense success influenced the tone and voice of many of the others that followed in the same genre. So it was a great relief to me to find that neither of the two books in Paul’s trilogy shared this fault. The first ‘An Italian Home’ describes the challenges and excitement of moving, getting established and becoming acquainted with your new adopted country, home, and neighbours – a dramatic and often traumatic process even if just moving to the next street let alone to a country where you have yet to learn the language. The second, ‘An Italian Village’, focuses on when the couple were already well established in Italy but needed to move, primarily for economic reasons, from their much beloved Moltrasio to nearby Argegno. Both books have an authentic feel with a sense of honesty and integrity incorporating some amusing incidents and engaging character sketches along the way.

The Expatriate Experience

Expatriates voluntarily expose themselves to a series of challenges of which the most significant must be the ability to communicate. Paul’s wife could speak Italian but he could not. He was not an employee of some large multinational with a workplace in which speaking Italian may have been desirable but not essential. He was and remains a self-employed artist needing to both understand a client’s commission and explain his response to it. They had also moved to Moltrasio, a small village on the west bank of the Como leg of the lake where the locals were more likely to have the local dialect as their alternative language rather than English. And he wanted and needed to become fully integrated within his new social setting. Achieving a degree of functional literacy must be the first hurdle for any immigrant and Paul does not shirk in describing how much a challenge that was – with its detrimental impact on his self-confidence.

Pre-Maastricht, an English expatriate went through exactly the same bureaucratic hurdles in obtaining residency rights as immigrants from any other part of the world. Paul and Nicola had a tough time obtaining the right to stay. Italian bureaucracy has not got the best of reputations. I had hoped that the UK’s ongoing membership within the European Union would mean never needing to queue up again at the Questura with multiple copies of the correct documents and a ‘marca da bollo’ of the right value. But no, following Brexit, Paul, Nicola and myself now need to return there again to obtain a ‘carta di soggiorno’ which is similar in name and intent to the original ‘permesso di soggiorno’ that they bravely queued up for so many years ago.

The issue of bureaucracy is though a mental trap for the expatriate since, back in the UK, a British subject has no need to obtain a ‘permesso’ for anything. But a foreign visitor does and their experiences in attempting to gain residency, let alone nationality, have been for years difficult and are only getting worse. And to make a slow underfunded bureaucracy even worse, the UK government deliberately set about making the immigrant’s experience more unpleasant by instituting the so-called ‘hostile environment’, a phrase that ex-Prime Minister Theresa May has belatedly come to regret using. As an expatriate/immigrant you are on the powerless side of the bureaucratic battle in whichever country you aim to settle. Until you have secured your rights, the ongoing sense of powerless is yet another blow to your well-being and self-confidence.

Libero Professionista

Apart from being an author, Paul’s main activity is as an artist specialising in murals as well as using trompe l’oeil effects to decorate furniture. One of his original reasons for leaving leafy Surrey was because UK fell into recession in the early 1990’s causing a major drop in the number of clients. He very quickly gained some commissions on settling in Moltrasio thanks primarily to the contacts Nicola had made years earlier when acting as an au-pair. Paul had immediately learnt the importance of personal introductions in allowing him to market his skills. Back in the UK he had been accustomed to present his portfolio to private galleries as the primary way of gaining commissions. He was told and quickly learnt that this was not a sufficient marketing technique here. In Italy one needs some form of personal contact, an established person who can recommend you to others. I have heard the same point made by other expatriate artists working around Como. Fortunately Paul’s wife’s contacts could provide Paul with the necessary entry amongst interior design architects.

He worked initially for a Como architect who gained him a number of rich but demanding clients but sadly also introduced him to a less scrupulous variety of business ethics. While cheats and scammers can unfortunately be found everywhere, they seem to stand out to a greater extent in Italy since they exist in direct contrast to the much larger number of selfless, generous people who dedicate time and energy volunteering for all manner of associations and social causes. Paul was being introduced to the Italian world of ‘bravi e stronzi’ or heroes and villains.

Heroes and Villains

Heroes and villains stand in contrast to each other. Villains are essentially sociopathic with the capacity to defraud or cheat without moral qualms. By acting almost entirely selfishly, they debase their human value. Heroes act on behalf of others to increase their quality of life through their organisational or inspirational abilities or simply through selfless acts towards others. Their human value goes beyond price.

If the defects in Italy’s judicial system provide scope for villains, then the existence of so many voluntary associations also provides scope for heroes. Paul’s villain was the Como architect. His hero was the leading light in the Moltrasio Pro-Loco association.

Many small Italian towns and villages have what is called a Pro-loco association whose aims are to enhance community life through organising social events or additional services to those provided by the local council. Moltrasio clearly had an inspirational figure behind organising carnival celebrations, Christmas crib competitions as well as coaching the local football team. Involvement with the Pro-loco association certainly helped Paul and his wife to integrate within their adopted community and in exchange Paul came to recognise the exceptional nature of their inspirational leader with his tireless energy.

Continuity and Change

Paul did not just leave UK due to the recession in the early 1990s but because he felt that UK society had lost an element of ‘continuity’. If I have understood him correctly I believe he refers to a continuity of custom and values, aspects of everyday life that pass from one generation to another made explicit through social events and ceremony. These are definitely aspects that are more identifiable in a small town or village, and Paul certainly seemed to relish living and integrating within a relatively traditional society. However change is a continuous given, and as we get older, the rate of change appears to get ever faster. For expatriates perhaps the most significant positive change since the 1990s has been the Internet and the rise of social media. Phone calls back to family no longer cost an arm or a leg as in the days of metered tariffs. Events in family groups can be shared in real time as with news and current affairs. Technology has even ameliorated some aspects of the local bureaucracy but by no means all!

Paul and Nicola themselves had to undertake a significant change once they had decided to buy a house on the lake. They found they could not afford what they wanted in Moltrasio but did find what they wanted fifteen kilometres north in Argegno. Their experience of moving and living in Argegno is the subject of Paul’s second book in his trilogy ‘An Italian Village’.

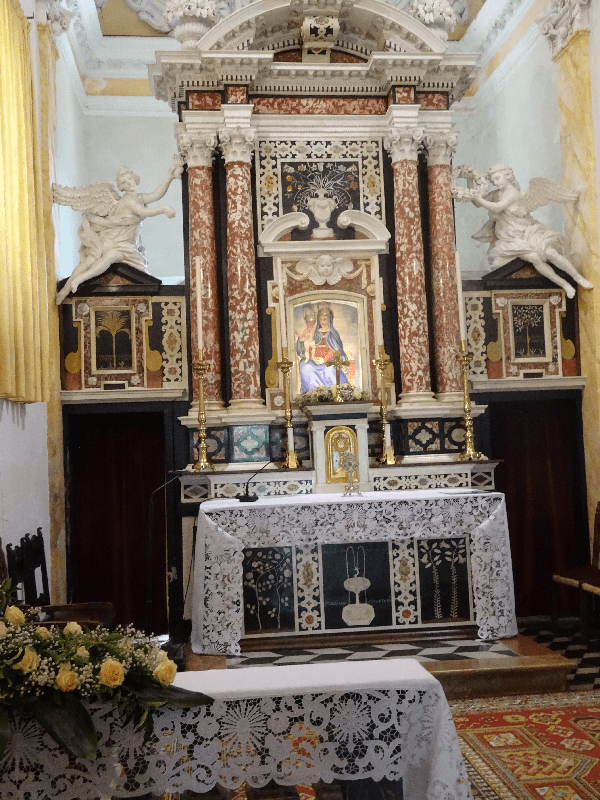

Argegno sits on the lakefront at the start of the Val D’Intelvi which runs horizontally from Lake Como towards Lake Lugano. The Val D’Intelvi has a long tradition in providing artists and craftsmen whose skills have gone to embellish churches all over Eastern Europe and Southern Italy. The first wave of craftsmen, known as the maestri comaschi, constructed churches in the Romanesque style throughout the middle ages. The second wave worked on the redecoration of church interiors during the Baroque period. Val D’Intelvi artists and artisans were used to paint frescoes and design plaster statuary. Paul learnt about the technique perfected by the artisans of Val D’Intelvi called ‘scagliola’ used to give the appearance of marble marquetry on altars.

Paul’s own skills in painting trompe l’oeil murals fitted into the tradition of Val D’Intelvi craftsmanship as did the resulting need to work away from home for prolonged periods. Val D’Intelvi craftsman might work away from home from Spring to Autumn in decorating a cathedral such as that in Passau (Passavia) in Germany. Paul’s Passavia was down on the Ligurian coast where he worked away throughout the summer heat in the company of two builders from Bergamo. Little was he to know that he would be participating in a traditional pattern of seasonal migration established in the area he had chosen as home as far back as the tenth or eleventh century.

Too Much Continuity

Paul was as keen to integrate as fully in Argegno society as he was in Moltrasio. But rather than involvement in the local pro-loco, Paul’s target here was to become a member of the inveterate band of pensioners that gathered daily around the main piazza’s fountain to gossip and put the world to rights. Most Italian small towns, villages or city districts have at least one location, usually a bar, where retired men gather to while away the hours until called home to eat at midday. Paul’s group in Argegno seemed to consist of retirees from the hospitality industry – from the many bars, restaurants or hotels that for years have met the needs of visiting tourists. As a result many had retained an enhanced interest in eating or drinking or both. They also shared in the migratory instinct of the Val D’Intelvi having spent time at some stages in their careers in working abroad, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Membership of this select band of societal ruminants required a heavy obligation to maintain a regular appearance around the piazza’s fountain and to accept the unchanging daily pattern of discourse. The repetitive continuity of the ritual discussions and the necessary regular commitment to them became even too much for Paul after a while. Apart from other demands on his time, he found the company was limiting its own horizons, becoming far too focused in time and place. This was just one further level in local immersion and continuity he could not sustain.

Conclusion

Now over thirty years have passed since Paul described his arrival in Moltrasio in ‘An Italian Home’. As a result his account has become slightly historical but perhaps all the more interesting as a result. As mentioned previously, he writes with honesty and humour avoiding all the standard pitfalls of an expatriate’s viewpoint, such as generalisation and cliché. All the traumas and excitements of the couple’s initial move to Italy were behind them when he describes their move to Argegno in his second book ‘An Italian Village’. It is here where he actually establishes his own home and, no longer over concerned in gaining local acceptance and without further challenges to his self-confidence, he can settle to the idyllic existence he must have had in mind when moving out from Surrey so many years ago.

For my part, his books engendered a whole series of personal thoughts on the expatriate/immigrant experience simply due to their authenticity – a response in marked contrast to that provoked by ‘A Year in Provence’. I am very grateful to him for that.

Further Information

All of Paul Wright’s nonfiction is available on Amazon and in Kindle editions. He is currently working on a novel set on Lake Como so look out for its publication early next year.

Further Reading

I have previously noted the positive results that can be achieved by small communities with an active pro-loco association, in particular Moltrasio. Please read Moltrasio: The Power of Civic Pride to see why it is well worth visiting this enchanting village.

The Maestri Comaschi and the work of the Val D’Intelvi artists and artisans feature in two previous articles which are Como’s Artistic Tradition – A Pan-European Legacy: Maestri Comacini and Stucco and Scagliola – Two of Como’s Baroque Specialities.

For walks around Moltrasio see Carate Urio to Moltrasio via Rifugio Bugone and for Argegno see Argegno to Argegno: Up and Down the Telo Valley

Not pulling any punches about A Year in Provence! But yes how refreshing to hear about an expat memoir that doesn’t shy away from the efforts of acquiring language and cultural literacy, and other barriers to regaining self-confidence in a new setting.

LikeLike