The entrance to Como’s Cimitero Monumentale Maggiore, with the cemetery’s church in the background.

Como’s Monumental Cemetery, the city of the dead, is a reflective microcosm of the city of the living – particularly of its art and architecture. As such, it is well worth a visit since no other location brings together in one defined space the city’s disparate artistic traditions and architectural styles from over the last two centuries. We recently visited the cemetery thanks to an initiative of the Como branch of the FAI whose volunteers took an intrigued audience around a selection of the more significant tombs and monuments. This article focuses on the work of some of the better known sculptors in a bid to illustrate the quality and the range of artistic styles on show but perhaps above all, to encourage those of you either living or visiting here to make it out to the Basilica Sant’Abbondio and across to the Cimitero Monumentale – the former for its apse entirely covered in 14th century frescoes and the latter to see exactly how Como’s wealthy bourgeoisie celebrated death.

Looking down one of the porticos that line the perimeters of the cemetery.

Monumental cemeteries, so named for the presence of monuments, took off in the early to mid nineteenth century across many cities in Italy. They arose partly due to the overcrowding and hygienic concerns of inner city graveyards prompting ordinances that prevented further churchyard burials and partly due to the growth in local civic pride. The demand for a ‘city of the dead’ was in turn fuelled by the growth of the population as a whole but particularly in the numbers of wealthy industrialists with their relatively large family dynasties established in a time when mortality rates were still high.

Looking towards the north east cormer of the cemetery and Campo E.

The need for a dedicated cemetery in Como was first considered following Napoleon’s edict of 1804 forbidding church burials – an edict that went ignored for many years. However numerous sites were considered until land was consecrated at the foot of the Parco Spina Verde just south of the Basilica Sant’Abbondio in 1813. The rectangular structure with a central chapel was designed in 1824 and then the final neo-classical design we see today with the porticos branching out from the central chapel was completed in 1841. As such Como’s Monumental Cemetery was established around the same time as those in Genoa and Brescia but earlier than the famous one in Milan built in 1866.

Map of the cemetery,

The Cimitero Monumentale is designed as a rectangle running north to south with its western edge lying at the base of the Parco Spina Verde with the Castello Baradello visible at its south western corner. Porticos run alongside all sides of the rectangle with additional porticos running east west to divide Campo B from Campo C and Campo D from Campo E. The porticos house the individual chapels which are mostly numbered. Directly in front of the entrance is the cemetery’s church and crematorium. There are additional areas to the cemetery beyond the northern, southern and western sides of the rectangle.

Neo-classical may have been the favourite design style for the cemetery buildings but the monuments themselves display a range of styles reflecting the changes in cultural fashion over the subsequent years. From the mid 1800s neo-gothic was the dominant style with some showing the influence of romanticism followed in future years by examples of realism, art nouveau, expressionism in the darker years of the First World War and some cubist influences. There are also examples of works by some of Como’s twentieth century artists and sculptors as well as those by Como’s two famous architectural sons, Federico Frigerio and Giuseppe Terragni. Thus the various styles of the monuments reflect the variety of the architecture in the city of the living. And some of the funerary sculpture has its equivalence in the city’s public places.

Statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi in Piazza Vittoria, designed by Vincenzo Vela who also designed one of the cemetery’s monuments.

The quality of some of the sculpture and artwork is one good reason for visiting the cemetery. Another might be to see the memorials to some of Como’s more famous names. For instance, the memorial that stands out on immediately entering the cemetery is that to Francesco Somaini who died in 1939. The chapel itself was designed by Federico Frigerio, arguably the 20th century architect who has most influenced the way the centre of Como looks today. However the impact here is the large scale ‘Pieta’ in bronze sitting above the chapel and sculpted by Giannino Castiglioni. Francesco Somaini was an industrialist who established his cotton mill in Lomazzzo in 1893 adopting a revolutionary factory design first developed in Manchester. His factory lies alongside the Lomazzo railway station and now houses the series of high-tech startups known as ComoNext. Francesco Somaini was a great sponsor of Federico Frigerio and paid for the construction of Frigerio’s Tempio Voltiano on the lakefront. His own grandson, also named Federico, was a local sculptor of some renown and has examples of his work elsewhere in the cemetery.

The monument to the Somaini family with its base designed by Federico Frigerio and the monumental sculpture by Giannino Castiglioni

The space for the Somaini memorial was gifted to the Somaini family in perpetuity and at no cost. This was a rare concession since almost all other chapels are on a 100 year lease from the municipality at a cost. If you tour round the cemetery you will see signs out on some of the chapels stating how the lease period has run out and needs renewal. Such are the vicissitudes of family fortunes and finances that some may no longer be either able or interested in maintaining the family vault.

Luigi Agliati

A common symbol, particularly amongst the neo-gothic monuments, is that of the grieving woman – similar in some respects to the Pieta’s depiction of a doleful Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of her son. On walking over to the church and following the portico to the right, you will come across Chapel No. 1 housing one such mournful lady.

An example of the grieving woman image. This is from Chapel number 59, created in 1890 and is the work of Ezekiel Trombetta

There are a total of eight works by Agliati in the cemetery. Agliati was born in Como in March 1816 and made a name for himself as a funerary sculptor. He was granted honorary membership of the Milan Academy of Fine Arts in 1860. He entered the competition for the design of Milan’s Monumental Cemetery in 1861 and was shortlisted as amongst the five best contenders. In addition to his other works in Como’s cemetery, he also has two works in the city’s Duomo, namely the monument to Cardinal Tolomeo Gallio (1860) and the bust of Bishop C. Rovelli.

Detail of the monument by Luigi Agliati in Chapel number 2

In the next chapel along, Chapel No. 2, there is one of the other works by Agliati dedicated to the memory of the Bagliacca family. At its base there is a well-sculpted marble bas-relief showing a kneeling and shrouded man reaching upwards towards the hand of a woman sat on a cloud with her three children. Her other hand is raised towards the sky where divine light shines out. This symbolism is easily interpreted and the plaque makes explicit that the dead man has gone to join his wife and their three children, all of whom died before him. However, to the left and behind the kneeling man, Agliati has included some less obvious symbolism in the form of a broken tree, to signify death, from which comes a blossoming bud as a symbol of resurrection.

Enrico Rusconi

Chapel number 46, monument created by Enrico Rusconi in 1896 and dedicated to the Segalini family.

Arguably one of the most striking representations of a grieving woman can be seen in Chapel No. 46 in a marble memorial to the Segalini family by Enrico Rusconi in 1896. The perspective employed in depicting the colonnaded portico in the background helps frame the grieving lady placed hugging the cross right of centre in the foreground. She is wearing a long dress with a finely embroidered shawl covering her head and then tied at her waist. The shawl is rendered in fine detail as is the lace work on the lady’s sleeves, revealing Rusconi’s craftsmanship. There are a total of six monuments sculpted by him in the cemetery whilst he is also responsible for the statue of Felice Cavallotti displayed in the front of the Istituto Carducci in the centre of Como.

Chapel number 65, Enrico Rusconi created in 1911 and dedicated to the Bazzi family

The delicacy of Rusconi’s work can also be seen in the monument to the Bazzi family in Chapel Number 65/66. He places the lifeless body in the bottom right of the scene with his head cradled by a woman. A small child comes out of the flowers at the body’s feet. The woman and the child are identified as the wife and child of Uberto Bazzi. The central female figure looking and rising upwards is a symbol of the soul rising to heaven.

Francesco Somaini

The grandson of the industrialist Francesco Somaini entombed under the ‘Pieta’ is a local sculptor who gained an international reputation and whose evolution of style from the figurative to the abstract can be traced here within the Monumental Cemetery. An example of his early work can be seen in the memorial to the Bettoni family in Chapel No. 7.

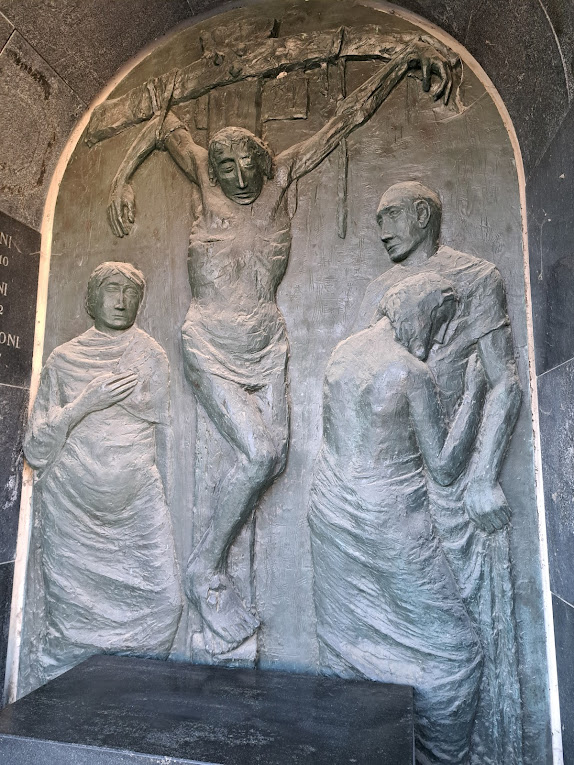

Chapel number 7. Monumnet by Francesco Somaini created in 1948 for the Bettoni family.

This bronze dated 1948 depicts a lifesized crucifixion scene with Mary to Jesus’s right and Mary Magdalene to his left resting her head on the chest of one of the disciplines. The representation of Jesus’s head with the clearly elongated nose alongside other sculptural aspects point to Somaini adopting some of Picasso’s early stylistic features.

Somaini studied at Milan’s Brera Academy from 1944 to 1948. The Bettoni bronze was commissioned once he had finished his training when he was still working figuratively but with an interest in expressive distortions as in his series of Horse Skulls which he exhibited in the same year.

We can chart Somaini’s development as a sculptor within the Monumental Cemetery by moving on to the northern corner of the portico running south from the entrance way. Here we can see Somaini’s monument to the Targioni-Beschi family commissioned in 1965.

Chapel dedicated to the Targioni Breschi family, designed by Francesco Somaini in 1965.

Here he uses the contrast in polished and oxidised bronze to give drama to a depiction of an exploding crucifix symbolising the power of resurrection over death. Somaini insisted on no words detracting his image and so the family had to purchase the adjacent space (seen to the left of the photo) for the family to include their dedication. The two sections of the entire monument are united by the common background of polished marble.

The last of Somaini’s monuments in the cemetery can be found in Chapel No. 27 in a monument dedicated to the Marinoni family in 1977/8.

Chapel number 27 dedicated to the Marinoni family and created by Francesco Somaini in 1977/8

Here again Somaini works with the contrast between polished and oxidised bronze in this dramatic presentation of a crucifixion. There are still figurative traces in this work in the delineation of the body but the abstract aspects provide the symbolic power of the polished image to stand out from the folds of the background. Here again, a scripted dedication would detract from the sculpture but the side walls give space to put individual plaques to commemorate the family members.

Somiani’s career took him to fulfil commissions abroad from the 1970s in Phoenix and Atlanta in the USA and in Paris in the 1980s. Closer to home he designed the Monument to the Weaver in 1990 for the silk industrialist Mantero near to one of Mantero’s factories on the lakefront at Menaggio. His work ‘La Porta d’Europa’ stands in the Bennet Shopping Centre of Montano Lucino, created ten years before his death in 2005.

Eli Riva

Memorial to Pope Innocenzo XI in Via Odescalchi created by Eli Riva

Another of Como’s much appreciated sculptors was Eli Riva who based himself for most of his professional life in Rovenna, the village above Cernobbio. He had little interest in the commercial art world preferring to focus on his own development of the artisan skills of so-called ‘direct carving’. This was a technique favoured by a number of modernist sculptors such as Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth in which the stone would be shaped without reference to previous clay or plaster models so as to allow the nature of the material to determine aspects of the final design. A good example of this technique can be seen at the grave of the Baragiola family in Campo D. The sculpture is formed out of the same block of granite that covers the family tomb. Riva has chiselled out of this block the form of a cross lying horizontally which is said to symbolise the body of Christ. Riva’s work developed from the figurative towards the abstract. The Baragiola tomb dates back to the late nineteen sixties.

Monument by Eli Riva created in the late 1960s by Eli Riva and dedicated to the Baragiola family.

In Campo C there is another work by Riva dating back to the same period. This is the monument dedicated to the Ciabattoni family. The five spectral figures are depictions of those from Dante’s Purgatory. Their ghostly quality is accentuated by the contrast in their crumbling appearance against the dark shining polished marble behind them. He apparently got inspiration for these ghostly images from some of the oxidised Gothic statues taken down from Como Cathedral before restoration.

Monument designed by Eli Riva in the late 1960s and dedicated to the Ciabattoni family.

Riva also designed one of the more recent monuments in the cemetery dating from 1978. It is the monument to the Azzimonti-Gioacchini family in Chapel number 60. It is a purely abstract work that symbolises the door or gate into heaven. The only way through the splits in the bronze surface is to become a spirit and thus go through into the afterlife. It seems born out of meditation and designed to provoke meditative moments for those looking on it. The actual dedication to the family is kept separate from the main work itself so as not to detract from its impact.

Monument designed by Eli Riva in 1978 and dedicated to the Azzimonti-Gioacchini family.

Riva is also the creator of the suspended statue of Pope Innocence XI (Benedetto Odescalchi) in the historic centre in Via Odescalchi.

Vitaliano Marchini

The artist Vitaliano Marchini was born in the Province of Milan in 1888 and died in 1971. He was forced at the age of twelve following the death of his mother to find work in Milan. He developed his love of sculpture by working in marble workshops where he learned how to carve. He was exhibiting from the age of eighteen, winning prizes in 1910 and 1912. He then went off to join the Alpini regiment for the duration of the First World War.

There ar two works by Marchini in the cemetery with one being a memorial for the Vigorelli family created in 1918 and a later work created in 1931 for the Onnis family. The later work avoids the harshness and tortured features of the earlier piece which was clearly influenced by the grim experiences of the First World War. The Onnis memorial, found in Chapel number 24, is softer and less pained.

Memorial designed in 1931 by Vitaliano Marchini for the Onnis family.

This bas-relief depicts Christ raising a figure from the dead, whilst pointing to the sky with his left hand suggesting the body is on its way to resurrection. The way Marchini has treated the figures with smooth and sinuous lines is in total contrast to the angular and distressed figures created for his earlier post-war monument.

Aldo Galli

Aldo Galli was born in Como in 1906 and is one of the famed group of local painters that came to be known as the ‘Astrattisti Comaschi’ who established an international reputation for themselves in the pre-war years for their abstract art. The other key members of this group were Carla Badiali and Manlio Rho. Aldo Galli trained as a decorator (in concrete and stucco) and as an art restorer. He never had the funds to pay for full-time art instruction but attended evening classes initially in Como and then at the Brera Academy in Milan. He worked on some of the stucco decoration for Milan’s Stazione Centrale. When he returned to Como in 1932, he met up with his old friend Manlio Rho and, alongside Rho and Badiali, helped established Como’s reputation as a centre for innovative art to compliment the equally innovative work of Giuseppe Terragni and Como’s other rationalist architects.

Aldo Galli’s memorial to the Frigerio family

We may question the capacity of abstract art to convey meaning in a sepulchral and symbolic context when considering his monument to the Frigerio family seen in Chapel Number 52. The abstract purity of this sculpture is moderated in the second of Galli’s works in the cemetery dedicated to the Longatti family in Chapel number 90. Here the materials are similar but the design is more obviously based on the religious symbol of the crucifix. In either case, it is good to see a couple of examples from the ‘Astrattisit Comaschi’ represented in the cemetery.

Aldo Galli’s memorial for the Longatti family created in 1970.

Giovanni Tavani

Residents in and visitors to Como have probably seen the sculpture shown below in the gardens of the Hotel Palace.

The sculpture of Paolo and Francesca in the gardens of the Hotel Palace by Giovanni Tavani.

It is by Giovanni Tavani, a local artist, and represents Paolo and Fraancesca, real life protagonists in a tragedy depicted by Dante in the Divine Comedy. Giovanni Tavani was born in 1934 as the son of the sculptor Pietro Tavani. (There is also a work by his father in the cemetery). He trained as an architect but on graduating devoted himself entirely to sculpture until his premature death at the age of 48 in 1982. He specialised in sacred art and developed a unique style based on medieval representations subjected to geometric revision. He has two works present in the cemetery. Back in the city, he designed the memorial to Giuseppe Sinigaglia, the Olympic rower, behind Villa Geno.

Giuseppe Tavani’s memorial in Campo B

Federico Frigerio

We have already mentioned the work of Federico Frigerio in designing the base (but not the sculpture) towards the entrance to the cemetery dedicated to the Somaini family. As perhaps the most influential architect in definiong how we currently see Como’s centre, it is no surprise that there are also examples of his work in the city of the dead. Arguably the most eye-catching is Chapel number 28 dedicated to the Cattaneo family. Constructed in 1923, here he uses fine materials to produce a highly decorated chapel with mosaics, metal gates and a marble sarcophagus.

Federico Frigerio’s design of Chapel number 28 completed in 1928 for the Cattaneo family.

Other examples of his work can be seen along the same side of the cemetery in the chapel designed in 1900 and dedicated to the Musa family. He also designed the chapel for the Walter family in 1930. This is easily recognised by the golden mosaic dome on the roof of the portico running alongside. The gates depict certain animals each of which had their own symbolic meaning in early Christian art. The two fish, being creatures that live underwater without drowning, represent life after death. The two deer drinking from a spring represent man’s desire for God. The two peacocks are symbols of eternal life and humility.

Detail of the mosaic in the lunette of the Cattaneo memorial.

Giuseppe Terragni

Como’s other great architect, Giuseppe Terragni, the ‘rationalist’ designer of the Casa del Fascio and other great works in the city, designed the two twinned chapels in Campo B. One of these has concave columns whilst its twin’s columns are convex.

The Terragni chapels showing the interplay of concave and convex forms – examples of sepulchral rationalism.

Giuliano Collina

Giuliano Collina was born in 1938 in Intra but moved to Como with his family in 1944 where he lived up until his very recent death on 14th November 2025. He trained and graduated from the Brera Academy. He did not specialise in sacred art but was always interested in the concept of the fallen angel and of angels in general who feature in both of his monuments within the cemetery. He dedicated most of his life to painting whilst also teaching design and art history in Como schools. In his later years he turned to sculpture. He made explicit his allegiance with the Transavantgarde movement which emerged in Italy and Western Europe over the 1970s and 80s. This movement turned its back on abstract art for a return to figurative representation with mythical imagery or symbolism. The first of his angel depictions is in Campo C, close to the Terragni chapels, in a monument dedicated to the Foidelli family and constructed in 1998. Here he presents us with two angels with the one bent over to the ground seemingly searching for a soul which the elevated angel had already sent on its way to heaven.

Giuliano Collina’s two angels in Campo C created in 1998 in a memorial for the Foiadelli family.

The other angel can be seen in Chapel number 37 in a monument constructed in 1996 and dedicated to the Pozzi family. Here the angel is taking the crown of thorns off the cross as if to end earthly suffering. Collina has incorporated the wood grain into the bronze structure of the cross as a gesture towards brutalism.

Giuliano Collina’s second memorial in the cemetery in Chapel number 37 created in 1996 and dedicated to the Pozzi family.

Pelicans

As one might expect in sacred art, religious symbols abound to depict the concepts of resurrection and eternal life or the emotions of loss and grief. Perhaps the most common is the lighting of an eternal flame to denote the ongoing spiritual presence of the deceased and the reassurance that he or she will not be forgotten, that the remembrance will be eternal. We have noted how different birds, animals or fish have their specific symbolic meaning but perhaps one of the more unusual examples is that of the pelican.

A pelican as symbol of self sacrifice and resurrection

The pelican is seen with its beak next to its breast. An ancient legend has it that pelicans are known to wound their own breast when food is short so as to feed their young. Thus the pelican came to symbolise self-sacrifice as in Jesus shedding his blood to save humanity. They also came to symbolise resurrection since, as with Jesus, the pelican survived its act of self-sacrifice. The very same image of the self-sacrificing pelican (but this time seen feeding her young) can be seen in the photograph below taken of a door to a house within Norwich’s Cathedral Close.

Conclusion

Conclusion

This article presents just a few of the monuments in the Cimitero Monumentale and has focussed on some of the artists who also have public sculptures in the city of the living. The artistic variety and quality of the monuments goes beyond those highlighted here. In particular there are some delightful art nouveau monuments as well as some striking realist sculptures. The Cemetery is definitely beyond the normal tourist circuit but then sadly, so is the nearby Basilica di Sant’Abbondio. The latter warrants a visit as a splendid Romanesque church with a fine set of surviving frescoes. The cemetery, the mini-city of the dead, also warrants a visit as a very distinctive reflection of the city of the living with its architectural features miniaturised and its variety of artistic trends presented in a sepulchral context.

Further Reading

For more information about Como’s group of abstract artists, read The Como Group of Artists – ‘Astrattisti Comaschi’

For more on the architect Federico Frigerio, read Federico Frigerio: The Face of Como

For more on Garibaldi’s links to the city of Como, read Garibaldi, the Battle of San Fermo and his Como Bride

For more on the group of Como rationalist architects including Giuseppe Terragni, read Como’s Rationalist Architecture 1: Around the Stadium

Thank you so much. Very informative and we will visit, having driven past several times.

LikeLike